ORIGINAL PHOTOS BY BRENDA JOHNSON (D-SPOT) AND ELI RADTKE; FILE PHOTOS BY BECCA DILLEY

We’ve all heard the stereotype before: Minnesotans think mayo is spicy.

There are plenty of riffs on similar images, but it all boils down to the same thing. Many of us have in fact seen that stereotype come to life via an aunt at a family gathering, or across the dinner table with a friend. A polite “ope,” followed by another round of waters and vigorous napkin dabbing.

With all the spice this state has to offer, I simply couldn’t sit around and let our reputation be besmirched. That is how I found myself staring down a wing that came with a warning that pregnant women or those with heart conditions shouldn’t ingest or even BREATHE around it. Before we tell that story, though, it’s important to understand where this stereotype comes from, how spice affects our bodies chemically, and the history of spicy foods in Minnesota.

Evolution of a Palate

Before diving into the spice, some necessary context: Minnesota’s native tribes were here first and that we live on stolen land. I will touch on how a foragers’ palate plays into our collective preferences a little bit later.

Minnesota was officially designated as a state in 1858. In the decades before and after that, there was a significant migration of immigrants from Europe. Scandinavian and Germanic populations settled Minnesota in startling numbers, enough so that around 70 percent of Minnesota’s current population can trace their ancestry back to these immigrants.

“One of the interesting things about Swedish-American food as we see it is that there are these old foods that are from a particular place,” says Swenson-Klatt. “For instance: potato sausage. You can get it at Ingebretsen’s, but Swedish people aren’t very familiar [with it]. It comes from one very small place [in Sweden].”

Many of the families and individuals that chose to immigrate to Minnesota were from rural areas and were slightly out of step with the way society was moving, says Swenson-Klatt. They were more religious and more conservative than the country as a whole. “They were looking for a new place, and people who agreed with them, and a place where they wouldn’t have to follow local politics and local religion,” she says.

This helped to preserve a different set of culinary traditions than what lived on in Scandinavia, giving Minnesota a distinct set of traditional Scandinavian foods as a baseline that mingled with other European (mostly German) immigration tastes at the time. This isn’t the reason for a mild palate stereotype, though. There are many strong flavors that come from Scandinavian cooking that are as flavor-intense as a hot pepper might be.

One such flavor is vinegar, a familiar taste to many Minnesotan palettes. In the United States, the vinegar we cook with is 5% acetic acid. In Scandinavia, cooking and pickling vinegar is often 10-20% strength, usually only found as a cleaning solution or in specialty stores here.

Swenson-Klatt points out that a lot of the flavors that have been preserved in the “Minnesotan” palate come from the fact that these immigrants moved here very poor. They would keep local traditions alive, and rely on mutual aid to keep communities running. Many of the natural, foraged flavors that Scandinavian cooking featured stayed similar thanks to a relatively similar environment, but the resources available here were different than in Scandinavia.

“There’s this stereotype that Scandinavians moved here because it looked the same. But moving to the plains did not look the same. That was a different place, and a different set of foods was available,” she says.

This included fish, mushrooms, herbs, and the like that we know today. These native Minnesotan resources are not known for their spicy profile, falling more under a savory bent. But one staple of this palate that often gets left out of the “spice” conversation is horseradish.

Root vs. Fruit

The 2021 Nobel Prize for Physiology was given to David Julius and Ardem Patapoutian for discovering the receptors for touch and temperature utilizing Capsaicin, the chemical found in peppers that makes them spicy.

Capsaicin is what turns your mouth into a portal to hell and causes your eyes to water. This chemical is found naturally in chili peppers and is commonly present in the traditions of cooking in warmer climates, as chili peppers take a lot of sunlight, a long growing season, and don’t hold up to cold very well. So, with our short summers, it stands to reason Minnesota’s traditional cuisine wouldn’t include a lot of capsaicin.

My rough “thesis” on why Minnesotans are often perceived as not being able to handle spice is because, traditionally, we are coded to handle a different form of spice.

Capsaicin is a molecule that easily binds to lipoprotein cells. Yeah, that sounded jargony to me too. Think of it this way: Capsaicin is an oil-based chemical. This is why we feel the heat in our cells, and often “spicy” feelings are felt in the tissues of the mouth that make contact with the chemical.

This is also why when you eat or prepare spicy foods, you shouldn’t touch your eyes or go to the bathroom without washing your hands THOROUGHLY. (This is a PSA from someone who has done that many times.) This is the same logic that pepper spray uses, capsaicin binding to our very fatty skin, eye, and mouth cells to cause pain.

Now here’s where it gets interesting. Have you ever bitten into a slice of sandwich with too much horseradish, or been too bold with the wasabi and felt that rush of tingling and pain in your nose? That’s because horseradish utilizes a different chemical to create that “spicy” feeling.

Allyl Isothiocyanate doesn’t quite have the ring that capsaicin does, but it can pack a similar punch. This chemical can be found in horseradish, mustard, and radishes, all staples of a more northern-leaning diet. Allyl Isothiocyanate is also different from capsaicin in the way our bodies react to it. You can rub a radish on your face all day, or exfoliate with a horseradish root, and besides weird looks from bystanders, there wouldn’t be any negative consequences. This chemical packs its punch when oxidized, which means that the cells that it binds to in order to trigger pain receptors are in the nose.

Because of the oxidization, and the fact that the chemical isn’t binding to the lipid layer of our cells when you get an especially strong nose full of Allyl Isothiocyanate, it’s going to hurt and make your eyes water, but only briefly.

So, when it comes down to a head-to-head comparison of what Minnesotans are traditionally used to, horseradish kicks hard right away but usually dissipates quickly, while capsaicin (usually) starts innocuously and builds to a high heat level that sticks around much longer. Could our stereotypes just lie in the fact that Minnesotans can handle spice, but for a shorter time?

In the meantime, since the 19th Century immigration surge, Minneapolis has been building up a slate of incredibly unique and eclectic restaurants, pushing the boundaries and conceptions of taste and palate. Many of these new restaurants were founded by immigrants hailing from regions of the world with entirely different spice traditions: Mexico and Central America, Southeast Asia, and East Africa, in particular.

Let’s take a look at where we started, and how the Minnesota food scene is heating up.

Twin Cities Glow-Up

Minnesotans have come a long way from horseradish and traditional meals, though. The term “foodie” was coined in 1980 by Gael Greene, a New York Magazine writer. If you look back on Star Tribune’s archives, from the best I could find, the first time that world made its way to our paper was in 1988. At this point many Minnesotan families were still getting their Mexican Cuisine fix from Ortega hard-shells at the grocery store and underseasoned beef.

Fast forward a few years, and the phenomenon of the celebrity chef was heating up the coasts. From Anthony Bourdain’s book success to the Food Network, food started becoming generally seen as something that was less of a labor and more of an artistic pursuit. This trend caught hold in the Twin Cities area, with Wolfgang Puck even opening a restaurant in the Walker Art Museum.

“I think people realized then that, ‘Oh, Minnesotans aren’t just eating hotdish around here,’” says Rachel Hutton, a Star Tribune features writer and former food beat writer.

While the celebrity “flash-in-the-pan” may have fizzled out quickly, Minnesota has had a deep bench of quality local talent that has been producing high-quality food for decades. “Oftentimes Minnesotans suffer from a little bit of a complex of being a second-tier city,” says Hutton. “We’re not the big coastal cities, but I would say rather than focus on that, maybe we’re not getting those top-tier Michelin restaurants, but who cares? Because our mid range is so good, and that ecosystem is so deep, I can have so many great meals at more casual places in town.”

While there isn’t any one event that changed food culture forever, there are a couple areas that I was interested in. One of those was the craft beer boom. The advent of beer halls that partnered with local eateries to provide a wider variety of flavor brought out more people, and caused some to broaden their palate. As Hutton notes: “A dad who only ever drank light beer would try an IPA and think ‘wow, this is pretty good!’”

As pivotal as the role of craft beer may have been, it happened in many different places. The more important thing to look at when we talk about how Minnesotan palettes are developing, and certainly getting more adventurous, is the culture of its cities, and by extension, the people.

Minnesota has a rich history of immigration and making a home for different groups of people. Just as the Minnesota palate got started in the first place, immigration is changing how Minnesotans at large experience food.

“What’s cool now is that we have a large enough immigrant population for restaurants to cater to the tastes of their home community […] Back in the day, if you had a Chinese restaurant, you were cooking for white people and toning it down,” says Hutton.

So now that we know chemically why spice is, well, spicy, and culturally we have a grasp on where our mild-mannered taste buds come from, it’s time for the main event.

Heat Advisory

You can’t just write about how hot food came to be, you need to put your money where your mouth is. (And ultimately, a few other anatomical places, but we’ll get to that later.)

I will preface this list of formidable foods with the fact that I can handle some heat, but I won’t be winning any awards for my tolerance anytime soon. So, ranked from “wow, I’m crying” to “legitimately concerned I burned through my stomach lining” here is the spiciest food I ate over the last month in the Twin Cities.

Thai Mango Salad ($12) | Bangkok Thai Deli | St. Paul | (Ordered spice level 5)

This salad from Bangkok Thai Deli was the least spicy thing I ate for this story and my roommates sat and laughed at me while I sat on the couch breathing heavily. This dish was probably the right level of casual spice for me, as it was a sweet heat that burned long after the fact.

The salad itself felt slightly disjointed; the mangoes didn’t quite sing out as brightly as they should, and the Thai eggplant combined with the crab presented a jarring texture combination. I thought the savory of the crab combined well with the sweet of the mango, and the crunch of the green bean was a good overall package, but the wetness of the salad turned me off to the overall experience.

Spice Meter: 8/10 spicy

Poltergeist Hot Sauce on a Fried Chicken Sandwich ($15) | Revival | Minneapolis

One of the things I love about Revival’s Poltergeist hot sauce is that it kisses you on the cheek while kicking you in the teeth. The base of this caustic concoction is golden raisins, so it offers sweetness and a flavor that isn’t all brimstone when you take your first bite.

The first time I tried Poltergeist, it was a small dollop on my finger. I survived, so I said: “Of course! Let’s cover a whole chicken thigh in it.” That experience, I can assure you, was much different. The heat of Poltergeist is, as you might hope, legitimately haunting. It’s a smokey, long burn that sits in the pit of your stomach and makes you feel like you’ve been holding your breath too long. One dangerous thing about serious heat in food is that before I knew it, I had taken down three beers attempting to cool my mouth off enough to breathe again, which activated a new set of sensations.

Spice Meter: 12/10 super hot. Not for the casual Minnesotan diner, but survivable.

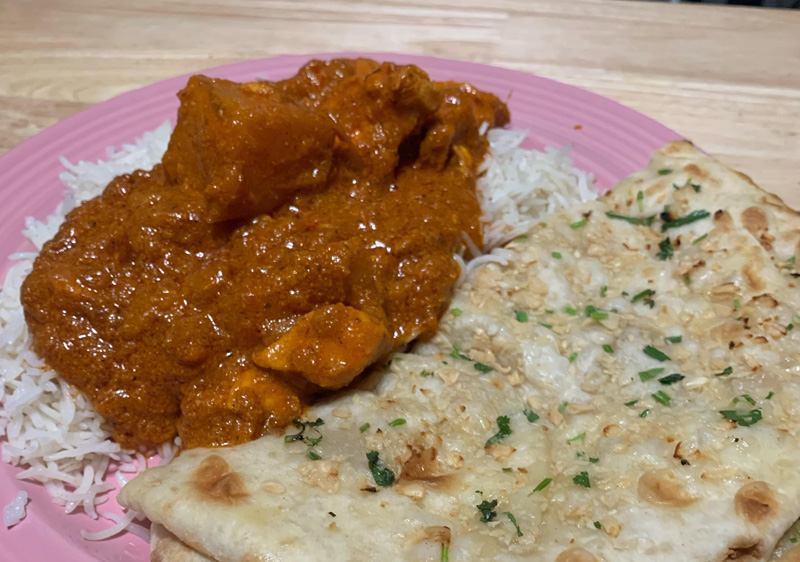

Chicken Vindaloo ($14) | Best Of India | St. Louis Park | (ordered “Indian Hot” with hot sauce)

When I called up Best Of India on a recommendation from a friend, and ordered a vindaloo (a dish that is already traditionally hotter than most) as hot as they could make it (yikes) and then added hot sauce? There was a tangible silence on the other end of the phone before I got back and: “Are you sure?”

Additionally, when I walked into the restaurant, I heard “Oh, he’s here!” from the back. I was earnestly warned to only put a small amount of hot sauce on the food, because it really was hot.

They were not joking around. The vindaloo hit my mouth like biting the inside of your cheek. It was an instant, knee-jerk sting that spread and only got worse. This hot sauce (I kept it in my fridge, and I use it SPARINGLY) and the vindaloo both had a distinctly bitter taste that is immediately followed by your pain sensors lighting up like a goddamn christmas tree. I ate entirely too much of it, opening weeping spicy tears and sucking on ice cubes at the table because the vindaloo was so good. The buttery undertone of the vindaloo complemented the rich, fragrant, and earthy overtones of the spices.

Spice Meter: 12.5/10. Didn’t kill me but bathroom breaks were interesting for a few days.

Witch Doctor Wings ($13.49 For 4) and Seppuku Wings ($42.94 for 4) | D-Spot | Oakdale

Sean Evans on Hot Ones brings Celebrities into his show to eat hot wings and ask them questions. The hottest sauce on that show, that brings nearly everyone to tears, is 2 Million scoville units (scientific way to say “F***, that’s hot”). By comparison, a jalapeño pepper is anywhere from 2,500-8,000 scoville. Military grade mace, the stuff that MPD hands out like candy these days, is 5.9 million scoville. The Seppuku wing at D-Spot is 5.7 million scoville.

The atmosphere at D-Spot matched the challenge, with a well-kept and spacious bar that had almost graffiti-like art on the walls that was as interesting as it was well done, plus a made-from-moss art… picture? Wall? on the way to the bathroom, and a grim reaper in the corner, watching over my journey into the underworld. It felt fitting as I was given gloves for the Seppuku wings and told not to breathe, touch, or manipulate anything with my hands. I couldn’t take the wings home, because D-Spot considers them a chemical weapon. So, I ate them.

Seppuku wings are so hot, that before I could try them, I had to eat the Witch Doctor wings, the hottest wing publicly available and already more heat than any 10 people should ingest in a month. Once I proved that I could not die from that, I had to SIGN A WAIVER releasing D-Spot of all liability, and WAIT 24 HOURS to think about what I had just signed up for. I have done less paperwork for minor surgeries.

When I tell you that a small portal to hell opened up in my mouth when I ate those wings, I don’t think I’m joking. The sauce is meticulously made over a 24 hour period, and crafted to inflict pain. The heat numbed my lips instantly. This was the kind of heat that had me checking my boxer briefs because I couldn’t tell if I had a malfunction. This was the kind of heat where I had to stop because due to nausea. I couldn’t tell you about the chicken itself, it was merely an envoy to guide the assassin to my intestines. Four hours after ingesting the wing, I had several spots that were burning because of contact from my fingers, and I had a stomach cramp so bad and so spicy it had me looking at my health insurance plan and praying to any god that would listen.

Spice Meter: 20/10. This was stupid heat. Hemorrhoid-inducing, gut-burning, years off your life heat. Concern for my health heat.

Spice Is Nice

So, does the shoe fit? Is mayo spicy for most Minnesotans? I think that there will always be a place for those that tear up when too much pepper goes in the pot, but overall Minnesota, and the Twin Cities specifically, has a thriving and diversified palate, just like those that live here. Swenson-Klatt put it this way:

“Any Minnesotan could choose to go through life and only ever eat things with salt, pepper, ketchup and mayo. You could do that. [But] we also have the choice to go and eat kimchi, and hot sauce, and other flavors out there.”

Or as Hutton put it: “That appetite for heat and more robust and unusual flavors will continue to grow, but Minnesotans will still have a hotdish and ham soft spot.”