If you didn’t know any better, you might think that the pandemic had passed, or that it never was. I walked the aisles of seven different south Minneapolis markets on the morning of Monday, March 23, with the idea of gathering observations for a pandemic journal of some sort. Instead, what I saw was one grocery store operating in life-or-death crisis mode, and six others operating more or less as usual.

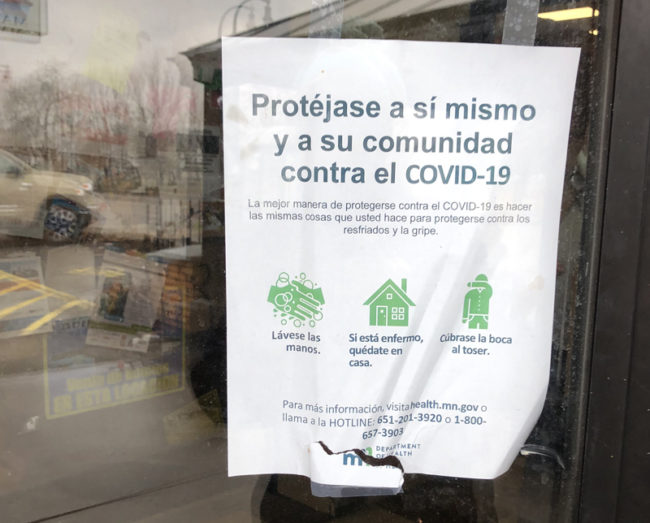

Three markets – Longfellow Market, La Alborada, and United Noodle – had signage at the door to remind customers about social distancing. Three other markets (Cub Foods at 2850 26th Ave S, Everett’s Foods, and Target at 2500 East Lake Street) offered customers and staff nothing whatsoever, or at least nothing that caught my eye on the way into the store.

Only one grocery market seemed to be taking the pandemic for what it most certainly is: a threat to the lives and health of millions of people.

Entering Seward Coop on Franklin Avenue felt like shopping in a time of real crisis. There was a one-in, one-out policy being enforced at the door. A small, widely spaced queue of customers waited for the green light from an employee before entering the store, the whole enterprise premised on decreasing the density of shoppers so as to afford everyone their twelve-foot umbrellas of safety.

Bold, bright lines of tape on the floor and plastic screens marked off safe distances for check-out and helped to shield the health of clerks, respectively.

In short: Seward Coop seemed to be aware that lives hang in the balance.

That there hasn’t been a statewide protocol instituted for all stores is surprising, if not worrying, considering how dangerous these workplaces have become.

LA ALBORADA | 1855 E Lake St, Minneapolis | “Mortality”

Everybody is gonna die. That’s a promise, not a threat. Human mortality is part of the bargain, and while no people in history have done as much to deny it, ignore it, and will it away as the Americans have, we’re still stuck. Death eventually knocks on the door.

Covid-19 has put a fine point on that prospect, and while we’re reacting reasonably well, there have been tinges of mania, irrationality, and desperation. For instance: buying out the ground beef, avoiding Chinese restaurants, and – please email me with an explanation for this one – buying years’ worth of toilet paper as though having access to this tree-derived butt buffer is somehow the shimmering skeleton key to life eternal.

At La Alborada, life went on. Customers held the door for other customers, the on-site restaurant wasn’t clearly open, but didn’t seem to be entirely shut down either, and tortillas, la base de la vida, were available.

La Alborada had milk, and eggs, without posted prices. It was out of flour and butter, but pleasingly wealthy in both tortillas and beans.

LONGFELLOW MARKET | 3815 E Lake St | “The Life and Death and Mass Death of Restaurants”

It has been suggested that 75 percent of restaurants may be out of business by the time the extraordinary part of the pandemic has run its course and most of the bodies have been buried. This seems like a back-of-the-envelope figure, but it makes a sound point: Many of the institutions that we love are going to go away, and the people who owned, ran, and staffed them will be hunting for work.

Whatever comes next, whatever spaces fill the void, it’s likely we’ll look back on 2008-2020 as a uniquely beautiful and robust period in American dining history. If we ever hope to regain that incredible cultural and culinary richness, we’ll need to put our money where our mouths are as a society – not just through individual consumer choices, but by taxing and spending in a way to support and restore a sector in deep crisis.

Longfellow Market had signs both at the door and at checkout, in a tasteful, serif font, admonishing customers to “Please be mindful of social distancing.” Without any definition or enforcement, this was a long way from a comprehensive solution, but it was also a far sight better than nothing.

Longfellow Market had milk for $3.80 a gallon, butter for $4.50 a pound, no flour, and eggs (organic) for $4 a dozen.

CUB FOODS | 2850 26th Ave. South | The Soul of Home Cooking

One of the best thing about being trapped in your house for an indeterminate period of time during a pandemic is the home cooking. If you don’t know how to cook at home, you have no excuse not to learn and evolve. If do you do know how, now is your time to shine.

I’ve found that despite the big blocks of available time, I don’t particularly want to stunt around and do intricate or beautiful pieces of food. Things that have been clicking:

SPAM musubi: Balanced, boldly flavored, and a perfect way to tap into those random cans of SPAM I picked up at Ha Tien before things got legitimately nuts.

Oatmeal raisin cookies: They scratch that “apocalypse sweets” itch, they’re easy to make, and they don’t leave you feeling nearly as gross as most other sugary desserts. I’d go so far as to say they are lovely fuel when eaten in moderation, and that they pair beautifully with single-malt Scotch.

Carne Adovada – The application of a blended, spiced chili paste makes this slow-cooked pork dish a bold, deeply flavored taco filling. You make it in bulk, there’s almost nothing that can go wrong, and it feels like feast when it hits the table.

Chilis (and other Latin foods) have always been part of the staples at the Cub just off of East Lake Street, and this unlikely spot is one of the city’s most vibrant global markets if you give it a chance.

Walk into Cub at a time of pandemic and you won’t be better educated about virology, but you will have the opportunity to buy an enormous bag of teff or barley flour. Numerous customers were sporting scarves wrapped around their faces, which offered little actual protection but did give the store a palpable (if low-budget) apocalyptic ambiance.

Cub Foods had milk for $3 a gallon, butter for $5 a pound, two bags of flour left for $1.79 per 5-pound sack, and no eggs.

EVERETT’S FOODS | 1833 E 38th St. | Family Time

My grandfather, also James Norton, was a supremely unsentimental man. As a physician and man of science, he was far more interested in unraveling how things worked than assigning any kind of emotional or moral judgement to their operation. But one thing I remember him saying is that he wished at times that he’d bought a farm, and kept his family close to him.

During quarantine, family breakfasts start at a leisurely pace and end whenever we wish them to end. We’re not racing out the door, we’re not packing bags full of supplies, we’re not exhausted at the end of a work or school week. We’re cooking together, and eating together, and being together. That, among all of this, is a quantifiable blessing.

Everett’s is nothing if not a neighborhood, family place, with a multi-generational butcher story at its core, and a mix of products that range from the prosaic to the artisanal to the house-made (meatloaf, etc.) It has always been one of my favorite places to shop, particularly for steaks, which they do skillfully and inexpensively, and frozen turkeys (which are Minnesota-raised and reasonably priced.)

Everett’s had butter for $4 a pound, but was out of flour, eggs, and butter.

UNITED NOODLES | Rationing, Shortages, and Profiteering

One of the stories you hear most often from World War II survivors – not that many are left – is that you had to struggle to get the staples of day-to-day life. Coffee, sugar, flour, eggs – it helped to know someone, and you never took them for granted. You found alternatives, you scrimped and saved, and you went hungry.

This is a way of life that anyone born after 1945 is almost completely unaware of. Sure, you might not have the money to buy what you need, but if you work that second or third minimum wage job, it’ll be within your grasp. It’s always there on the shelf.

It’s not there on the shelf right now, and while we’ve been assured by authorities that the supply chain is just fine, thank you, the crackdown on immigration and relentless advancement of global warming may make universal and affordable availability of all varieties of food a fond memory.

Rationing is meant to ensure that all goods are shared and everyone gets a little of what they need. Whether a free market-to-the-death government can ever steer its way around to rationing remains to be tested, but let’s collectively hope that we don’t get there.

As for profiteering: In late-stage capitalism, profiteering may not even exist. If the supreme good is maximizing gain through the use of the marketplace, what shame is there in charging $50 for a bag of flour or a container of hand sanitizer? Minnesota’s governor Tim Walz has taken action to prevent profiteering, but depending on how things develop, it may become a way of life.

You don’t appreciate the legitimate bounty – the variety, the depth, the sheer entertainment factor – of a fully stocked grocery store until you see the other side of things. United Noodles certainly isn’t stripped of options, but it’s hurting, and its masked (sometimes double masked) staff emphasize the point that things have changed.

United Noodles had Lactaid “milk” available for $10 a gallon, and no eggs, butter, or flour that I could locate. To its credit, it still has a robust selection of noodles and ramen kits.

SEWARD COOP | 2823 East Franklin Avenue | Food and Connection

Just as the reality of the pandemic was beginning to break, I was lucky enough to get together with friends from around the country and city for our annual celebration of Febgiving, a Thanksgiving in February that was designed to chase away the evil and loneliness of a northern climate winter. I can say “lucky” because nobody at either celebration seemed to be sick or has gotten sick since, although (obviously), that was more due to luck than any particular design. It will be a long while before we enjoy that kind of crush of personal contact again – the hugs, the toasts, the whispered asides, the cheek-to-jowl laughter and feasting. Food is at the heart of that kind of connection, and that’s the thing we’re all missing, and wondering about, and – on a sunny, positive-vibes kind of day – looking forward to seeing return.

So connection may the secret sauce for hospitality, both personal and professional. It’s also what makes for robust defenses in a time of crisis. Seward Coop had an employee at the door not just moderating the flow of customers, but talking about what precautions the store was taking, and why. It felt terrifying at first, but then once you got your head around the end goal, the lack of this kind of procedure is the thing that is baffling and galling. If Seward Coop is overreacting to the pandemic, there will be no harm done. And if they’re reacting adequately, it is critical that other stores learn from their example and catch up.

Seward Coop had milk available for $4 a gallon, butter for $7.50 a pound, flour for $7 a five-pound bag, and eggs for $4 a dozen.

TARGET | 2500 East Lake Street | Survival and Renewal

Restaurants are as mortal, fragile, and resilient as the humans who make them up. The name, the menu, and even the physical place may die, but if the people live to fight on another day, the spirit will return. One of the most challenging aspects of the coronavirus pandemic has been that the already uncertain hospitality industry has been thrown in a level of uncertainty so many times more intense than before.

Here’s a thin silver lining: the rise of smarter delivery, increased takeout options, and widespread adoption of online ordering will make the restaurants that survive (or reboot) that much stronger, and will help them to distance themselves from the expensive and sometimes destructive influence of 3rd party delivery services.

The change will come from above, from big corporate chains, but it will also come from below, from the nimble mom and pops. If shopping at pandemic-era Target was indicative of anything, it’s that being big isn’t a guarantee of speed or quickness to adapt – the Covid-19 footing of the comparatively tiny Seward Coop shone by comparison.

Target had milk for $3 a gallon, butter for $3 a pound, and no eggs or flour.

Editor’s Note: James Norton was laid off as food editor for the Growler Magazine last week along with all of his coworkers. This post doesn’t represent a reboot of Heavy Table, but is an opportunity to continue doing journalistic work during an extraordinarily challenging time in history.