For adventurous food lovers, a visit to the Minnesota State Fair is a treasure hunt for novelty. Some make it a tradition to seek out and sample first-time treats, playing a guessing game to identify which will be the culinary equivalent of a one-hit wonder and which might become a classic hit.

But those who want an increasingly rare taste of America, they might consider plopping down at a church dining hall — while they still can.

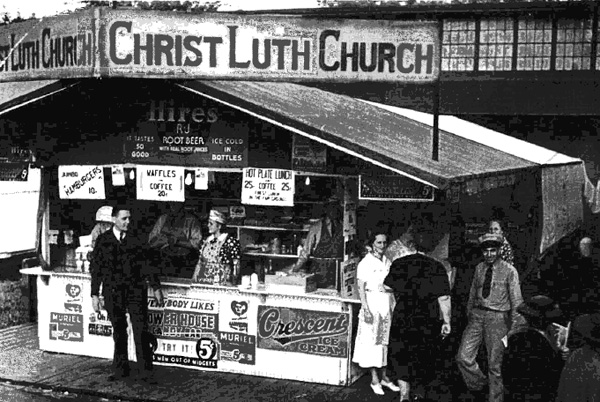

“The tradition of good food at the Fair started with these diners,” says Dennis Larson, who manages the licensing of food vendors at the Minnesota State Fair. “Fast food was sort of invented at the Fair, and that’s what flourishes here.”

According to State Fair records, there were 26 church-run establishments in 1955. Forty years later, in 1995, six remained. This year, it’s down to three, and counting. The 2011 Get-Together will be the final year for the Epiphany Country Diner. After serving fairgoers holy chow for 45 years, the Coon Rapids-based Epiphany Catholic Church is calling it quits.

“It was not a decision made lightly or without significant heartache,” says Sue Lewis, a longtime church member and volunteer. “We are not blaming anyone for our closing. Our food is simply not as desirable as it used to be.”

“That’s so sad!” says James Matheson, when he heard about Epiphany’s pending demise. Matheson has worked the Fair for the past dozen years, first as a broadcast technician and more recently in promotions. He’s tucked into many a meal served by church volunteers. “I think about the hot turkey sandwich all year. It’s true comfort food. And you can sit down for a minute to eat.”

In 1967, $1.35 bought a full dinner at the Epiphany Diner. A piece of pie tacked 20 cents onto the cost.

This year, platters featuring roasted-on-site turkey or beef, real mashed potatoes and gravy, a roll, and a scoop of green beans for color will cost $9.50. Epiphany will also offer burgers, wraps, a $5 walking taco, and a full breakfast; $8 buys scrambled eggs, pancakes or toast, hash brown,s and a choice of meat hot off the griddle.

There was a time when such hearty Fairground fare was in demand. With roots as an agricultural exposition, farm families were once the essential visitors. They made the annual pilgrimage to the Cities to show their sheep, marvel at gargantuan pumpkins, and size up equipment on Machinery Hill. Their idea of a treat was the familiar gravy-drenched fare they ate in their small-town cafes; they sought out the church halls for their home-cooked breakfasts and country-style dinners.

Today, riding lawn mowers outnumber combines on Machinery Hill. The Fair’s research shows that today’s typical visitor is from the metro area. Most food vendors offer a single product rather than a choice of heaping plates. Visitors who might relish meatloaf and mashed potatoes at home prefer a deep-fried, chocolate-dipped, spiral-cut spud when strolling the Midway.

Like other food vendors, the church dining halls must run commercial kitchens and submit to health and safety regulations.

“Years ago, women in the congregation would make food at home and bring it to the Fair in roaster pans; it was free money for them,” Larson says. “Now it’s a lot of work for not that much of a profit.”

Senior Day is always a big day for the church halls. But it’s not enough to be popular with oldsters and the 3,000 eaters who make up the State Fair’s daily work force.

“People who eat what we call ‘the fun food’ are here for a day,” says Larson. “If you’re here all the time, you want meat and potatoes. But there aren’t enough of us for the churches to make it with those numbers.”

“When we open up at 7am, we still have a line,” says Carol Logeais. She started volunteering at the dining hall run by the Salem Lutheran Church during the Eisenhower administration. Now 79, Logeais and her husband faithfully chaired Salem’s State Fair operation for many years, often spending all 12 days behind the counter.

At Salem Lutheran’s 60-seat diner on the northeast end of the fairgrounds, volunteers wear aprons stitched by elderly church members while they ladle up bowls of homemade pea soup, hand-pack the Swedish meatballs, and pour the fresh-perked egg coffee that’s traditional with the Uff-Da set.

“People either love it or they hate it, and I can’t say I care for it,” says Logeais of the signature brew, made by pouring whipped eggs over the grounds. “We still charge just a dollar. We’ve had some hot meetings about that. Some people think we shouldn’t give a never-empty cup, but I think it that’s how it’s always been and how it has to be.”

Salem Lutheran has changed far more than the made-from-scratch recipes. Based in Camden in North Minneapolis, the church served middle-class, Scandinavian worshipers in 1949 when the diner opened as a tent pitched over a dirt floor. Today, it’s an inner city congregation with an engaged youth ministry geared toward the neighborhood’s at-risk youth.

Like other churches with State Fair dining halls, Salem Lutheran has struggled to find enough volunteers to keep the operation staffed. The church now partners with three suburban Lutheran congregations to recruit the 50 workers needed to run the diner every day of the Fair.

“They sign up to support our ministry, and we’re very grateful,” Logeais says. “It’s a great intergenerational experience for all of us. The volunteers work side by side with our youth so they see who benefits. A lot of them want to do it again, they like our kids so well.”

After expenses, Salem Lutheran’s operation generates between $20,000 and $25,000 a year. Proceeds from the Epiphany Diner provide that parish with less than one percent of its total income.

“While we do turn a profit each year, it is becoming increasingly difficult to do so,” Epiphany’s Lewis says. “Running the diner at the Fair was never so much about the money as it was about fellowship and having a presence at the Fair. Our primary mission is not to serve up a good meatloaf dinner and make a buck on it. Our mission is to serve and glorify God.”

In 2009, after 52 years at the Fair, St. Bernard’s Bulldog Lodge served its last turkey dinner. Like many other vendors, the St. Paul-based Catholic church owned its State Fair diner, but not the land it occupied. The parish sold the location back to the Fair, which sought a new operator for the prime site. Fifteen vendors lined up for the right to take over spot, located just inside the main gate. O’Gara’s Bar and Grill, the St. Paul Irish landmark, won the heated bidding war. Last year, “O’Gara’s at the Fair” premiered. The humble church diner was unrecognizable; it had been transformed into an elegant European-style pub, complete with an antique bar, a menu featuring burgers, sweet potato tater tots, and Irish fare, plus 10 beers on tap.

“That corner had become kind of sleepy,” says the Fair’s Dennis Larson, who was part of the panel that selected O’Gara’s. “O’Gara’s reinvigorated it into a profit center.”

The State Fair gets a 15 percent cut of the gross earnings of every food concession at the Fair. In its first year of operation, O’Gara’s took in almost five times what St. Bernard’s had garnered in the previous year.

By contract, the Fair regulates precisely what all vendors may serve and sell. The church halls are obligated to operate traditional, full-service, diner-style operations.

“Per our agreement with the Fair, we are constrained on being able to change our menu or setup significantly enough to attract the kind of business we need to succeed,” explains Epiphany’s Lewis. “We did want to serve alcohol; however, that was not approved. We wanted to close early because we are significantly slower at night and that was also denied.”

Ironically, in 2012, it’s likely the Epiphany site will be taken over by the Minnesota Farm Wine Association, which has had a smaller presence in the adjacent Agriculture-Horticulture Building.

“That’s been their incubator,” says Larson. “They’ve developed a loyal audience that they will bring with them. They will promote a new Minnesota agricultural product, offer education, and do some wine pairings. It’s what our younger patrons are looking for and will gravitate to.”

Larson says the food at the State Fair is simply driven by market forces.

“People vote with their money, and we can count the votes,” he says. “They’re not voting for the church diners. Through no fault of their own, their day is passing. We love to have ’em and we’ll never kick ’em out, but at some point they have to decide if being here makes business sense for them.”

As for the remaining church dining halls, Carol Logeais says, they haven’t quite given up yet. “We’re going to stay as long as we can, but every year, we wonder if it will be our last. Every year we survive, it’s a miracle.”

A very well-written and well-researched article. Great job.

It’s interesting to see how the Fair has gone from what it was decades ago to essentially being a Minnesota version of an Oktoberfest-style celebration.

We took the time to make a first-ever stop at the Salem Lutheran Dining Hall at the fair on Sunday. I ordered a breakfast sandwich that was horrible (prepackaged gas station style), but the cinnamon roll and pancakes were tasty, and the egg coffee was fascinating. The atmosphere was downright cozy and a great escape from the madness outside.