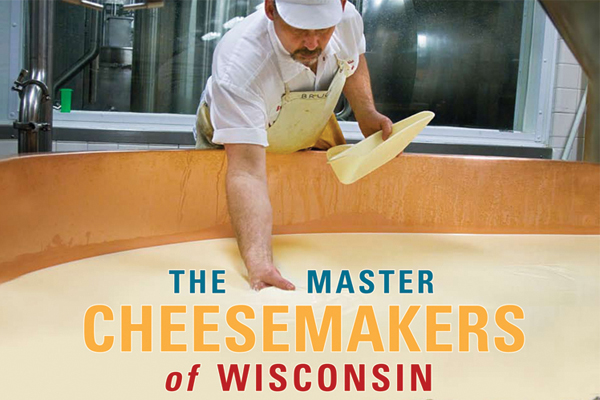

It took a stint living out East for native Wisconsinites James Norton and Becca Dilley to realize how special their home state’s dairy business truly is. And that curiosity, steeped by a conversation with a cheesemonger on the West Coast, led the pair (The Heavy Table’s editor and contributing photographer, respectively) to collaborate on a new book that showcases the people behind Wisconsin’s world-class cheeses. Writer Norton and photographer Dilley spent their newlywed year crossing the state to interview master cheesemakers — long-time cheesemakers who have taken their craft to a higher level by completing an intense training and certification program sponsored by the Center for Dairy Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board. The result is The Master Cheesemakers of Wisconsin, published by the University of Wisconsin Press, in which the people who craft Wisconsin’s famous cheddars, colbys, and limburgers get their turn in the spotlight.

It took a stint living out East for native Wisconsinites James Norton and Becca Dilley to realize how special their home state’s dairy business truly is. And that curiosity, steeped by a conversation with a cheesemonger on the West Coast, led the pair (The Heavy Table’s editor and contributing photographer, respectively) to collaborate on a new book that showcases the people behind Wisconsin’s world-class cheeses. Writer Norton and photographer Dilley spent their newlywed year crossing the state to interview master cheesemakers — long-time cheesemakers who have taken their craft to a higher level by completing an intense training and certification program sponsored by the Center for Dairy Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board. The result is The Master Cheesemakers of Wisconsin, published by the University of Wisconsin Press, in which the people who craft Wisconsin’s famous cheddars, colbys, and limburgers get their turn in the spotlight.

How did the book get started?

JAMES NORTON: Becca and I lived in Boston, and we’d be invited to a party and we’d bring cheese because we’re from Wisconsin and we know cheese. So we’d kind of find ourselves in the position of defending cheese or explaining cheese, which affirmed our dairy heritage. And then we’d moved to Minneapolis and Becca was doing a cross-country trip and I met her in San Francisco. We went to the Cowgirl Creamery, which is a well-known and much-loved cheese shop in the Ferry Building in San Francisco. And the woman who worked as a cheesemonger happened to be a blogger and a Minneapolis native. So we started talking a lot about the Midwest and a lot about cheese, and it really got us going on the subject.

BECCA DILLEY: And I had heard about the master cheesemaker program and we were talking to her about that, because there were several master cheesemaker cheeses available there.

NORTON: And we were driving from San Francisco up to Portland, and I think I might’ve said, “It’d be really interesting to meet all the people who are master cheesemakers.”

DILLEY: You know, who are these guys who love cheese so much that they go back even after they’re successful to learn more about cheese?

NORTON: And it occurred to us, well, I like to write, and you like to take photos. What if we teamed up and made a book about it? I put together a proposal and pitched it to University of Wisconsin Press and they pretty much immediately were like, “Yeah, come on in, let’s talk about this, and see if we can make it happen.” And we brought in the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board early on, and they supported us financially and in terms of setting up interviews, and that was really instrumental. We did most of the research the winter of 2007 / 2008.

When you presented the proposal to the UW Press, were they intrigued that you wanted to focus on the people rather than the cheese?

DILLEY: The Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board was really interested in that aspect, and I think the UW Press to a certain extent, because it is different from any other books they’ve done. The UW Press, in particular, has done more, like, history of cheesemaking in Wisconsin books. Several of those are quite good, which we reference, and they’re very exhaustive. I think they saw this as having a little bit more of an appeal to people who are not necessarily interested in the cheese history of Wisconsin.

NORTON: It was almost a deliberately non-academic book. It’s a contemporary documentary survey. A snapshot, if you will, of the industry, told through the biographies of individuals. I don’t know that anyone else has done a book quite like this. Because I think people get very caught up in the cheeses. And I think that’s a totally reasonable way to go and I absolutely understand why people pursue those books, but this is really about the generations of people, culminating in these amazing masters who work with the cheese, and it’s their stories and their perspectives and their challenges.

Being lifelong Wisconsinites, did you think you knew cheese before you did this book?

DILLEY: I thought I knew cheese before I went to Boston, but then I moved to Boston and we would bring cheese over and people would be like, “What’s a gouda? What’s the difference between this and this?” That made me a lot more curious about the history of Wisconsin cheese, and that’s how I found out about the master cheesemaker program.

NORTON: I’m not even sure if I really know cheese now. It’s such an incredible field. It’s a lifelong pursuit to really understand cheese. And the more experienced the cheesemakers are, the more likely they are to say, “I don’t know how it works, it’s totally crazy.”

DILLEY: There were a few people who were like, “It’s magic every time.”

NORTON: And they’ve been working with it for 30 or 40 years. The thing that makes a great cheesemaker – this is the common element among the people we interviewed – is this tireless quest for the X-factor, this little thing that tilts a cheese from good to great. What makes a cheese go bad? Was it the humidity? Was it the kind of cow’s milk we were using? Was it the time of day? What was the variable that changed this cheese, and how can I isolate it and reproduce it? They’re like scientists in that regard.

Besides the quest for the X-factor, what other commonalities did you see among the cheesemakers?

NORTON: I think one of the commonalities is work ethic. They have an incredible, old-fashioned, country work ethic where they don’t mind putting in 12 hours a day, six days a week or seven days a week, in some cases. They’re up for that challenge. They do it day in, day out, year in, year out. They’re just tireless. And cheesemakers kept telling us, “Yeah, it’s hard in this young generation to find people who are willing to work these hours and put in this kind of labor. It’s not a glamorous job, it’s not a super well-paying job.”

DILLEY: You often start at 6am. Or 4am.

NORTON: It’s not like your only choices these days are farm or cheese plant — which they were for a long time for a lot of people. So getting quality, hard-working people is a real challenge.

Were the cheesemakers excited when they heard about the project?

NORTON: Everyone opened their doors to us and showed us around. With few exceptions, they were not very guarded about it. They didn’t mind us snapping photos wherever, asking questions about whatever. It was sometimes fun, too, to interview guys at bigger plants because a lot of them had never really gotten the chance to tell their story.

DILLEY: Even though they’re often third- or fourth-generation cheese makers. Yeah, they don’t really get the opportunity to chat about it as much, because they’re not standing over a vat for 10 hours in a small place.

NORTON: But what’s interesting is that more and more these days, big plants are experimenting with, let’s try a pasture-grazed cheese, let’s try a mixed-milk cheese, let’s try a cave-aged cheese. There’s a real willingness to experiment in terms of a variety that wasn’t true for a long time. It’s part of the artisan renaissance right now.

DILLEY: In general in Wisconsin, they’re building more on a farmstead cheese model and trying to build more of these smaller, artisan cheese places and the big cheese plants are also kind of embracing that idea also.

NORTON: One of the really neat things about Wisconsin we noticed when making the book is the institutional support for cheesemaking is really strong. And you’ve got something like the Center for Dairy Research, which is a clearinghouse of information between private industry and academia and frontline cheesemakers. And everyone can ask questions of one another, “I’ve got this problem with my cheese, I don’t know what’s going on.” And the CDR will say, “That’s interesting. We’ll have an academic look at it.” Or, “Oh, you’ve discovered something new, we can figure out how to make this into a business proposition.” It’s a really cool, 20-plus people nucleus for dairy knowledge that’s at the University of Wisconsin.

When you set out to write the book, did you think your reader would not necessarily be a cheese lover?

NORTON: It’s not a food snob book. I view it more as a book about Wisconsin than a book about food. Obviously, the cheese is key player. We do tasting notes, we do write about cheese constantly through out it. But I saw it as more of a cultural documentary than pure food book. I think anyone from Wisconsin, I hope, would find it to be a good read, or someone from Minnesota or Illinois or anywhere that’s accessible to Wisconsin who is familiar with the lifestyle and the region.

DILLEY: I think it appeals to people who are just interested in having a connected view of where their food comes from.

What did you learn that surprised you?

NORTON: What was interesting to me was the amount of knowledge and sophistication required to do big commodity cheese operations that run 24 hours a day. Because you’d think you must just go in and hit a button and the cheese gets made. And to some extent, that’s true. Everything’s automated, computers play an important role, and the cheese line always keeps moving, there’s a lot of pressure there. But there’s some incredibly sophisticated sort of troubleshooting that’s involved in that. And the guys who are in those big plants have a lot of specialized knowledge and they’re really facing a challenge because the younger guys coming up in those plants tend to work one station, only know one thing, whereas the guys who’ve been there in the supervisory roles often came from smaller farmstead cheese backgrounds and really get the holistic idea of how cheese gets made.

DILLEY: If you’re the guy running the pasteurizer, to large extent, you do just press the button. But the master cheesemakers there do need to have a holistic view of it and do the troubleshooting. And it’s even a tighter, much more stressful way to do the troubleshooting because of the quantity, but also because they set up their schedules so that every 30 minutes a new vat has to come in. So you have a limited time to address and correct those problems. It’s really wild to see them do that.

If you could pick one thing you would want a reader to get from the book, what would it be?

DILLEY: Just an appreciation for that seemingly simple thing that’s so complicated and has such a rich history and is delicious but also crazy complicated. There’s so much knowledge and history and tinkering going on.

NORTON: I’d like people to come away with an appreciation for the intelligence and artistry of these guys, just how difficult it is to be a master cheesemaker, and how much real perseverance and artistry goes into it. It really is an art form. And it really is something very few people can do well. And we came away with a great deal of respect for the cheesemakers. It’s funny – even Wisconsinites say, “Oh, cheese, it’s easy.” No, no, it’s not easy! It’s insane how difficult it is.

Wisconsin’s cheesemaking is world-class. And you see that from the medals that Wisconsin’s cheeses win in international competitions all the time. There’s this really irritating idea in the Midwest, this inferiority complex, that if it’s not imported it can’t be all that good. But the beer around here and the cheese around here, and some of the charcuterie and sausage, if you’re at the right places – it’s world-class and we should celebrate it. Wisconsin cheesemakers are second to none and should hold their heads high among the French and the Danish and the Belgians and the Italians. And I hope Wisconsinites read this and realize, we’ve got a treasure here.

Norton and Dilley will discuss The Master Cheesemakers of Wisconsin at Magers & Quinn, 3038 Hennepin Ave. S. in Minneapolis, from 4:30 to 6pm Sunday, November 29. Naturally, cheese (and wine) will be served.

Masterful! Congratulations!

Do you know of any MN or WI cheeseries that give tours?

way to go Jim and Becca!

Looks like an excellent book – well done!

On another note, would anyone else feel better if these dudes wore gloves? There’s a lot of arm hair going on with the Master Cheesemakers…

Well done. But where’s the SPONSORED tag? ;)

Congratulations. It looks excellent.

Alex – you can order a map from the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board that includes cheese-tour locations. http://www.eatwisconsincheese.com/wisconsin/travelers_guide.aspx

GREAT article, Jill. I would love to read this book!

Dear Friends of the Author,

If from here on in we could all collectively keep comments on a more observational (as opposed to purely laudatory) level, that would be much appreciated.

Best Regards,

James Norton

Editor

Just sayin…

Hardy har. Adam Platt, ladies and gentlemen, single-handedly laying to rest the rumor that monthly magazine editors have too much work on their hands.

Sorry, couldn’t resist a hanging curve like that one.

Congrats on the book!

about the arm hair, those would have to be formal length opera gloves then… oh well, extra protein

Adam Platt, ladies and gentlemen, single-handedly laying to rest the rumor that monthly magazine editors have no sense of humor. Well, kind of laying to rest.