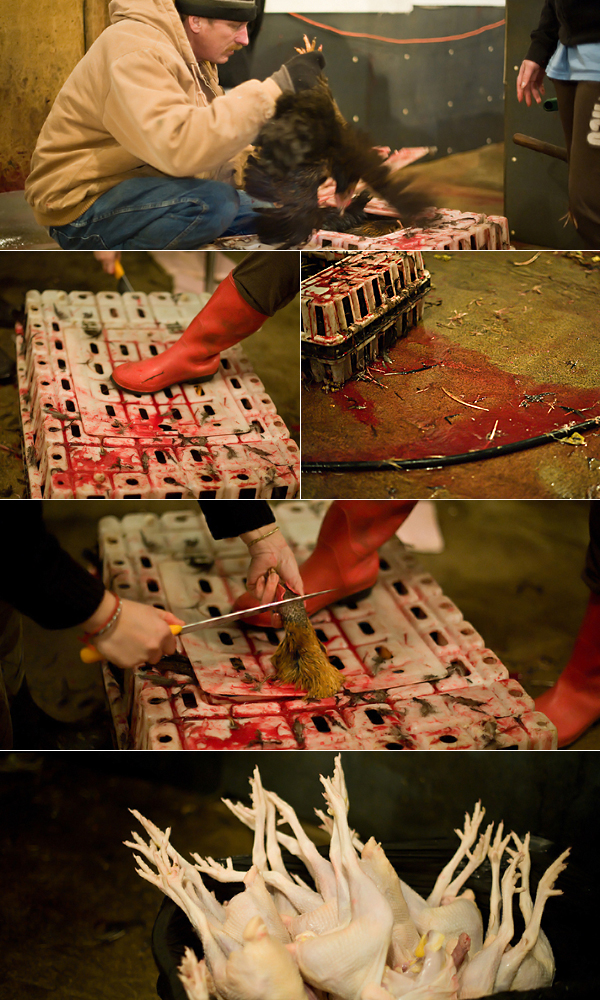

Editor’s note: Readers may find certain descriptions and photos included in this story to be unsettling.

The choice used to be simple: Either you ate meat or you were one of those new-age granola types who had nothing better to do with their time than wail about the poor animals who died to support such a degenerate habit. But every new blow to the conventional meat industry inspires a new option – a new way of turning your back on the modern mass-production of meat.

Those who fear the now-routine E. coli outbreaks in hamburger choose not to eat ground beef, or choose to grind it themselves. Those appalled by the treatment of confined animals choose to eat meat only from those that range freely. Those skeptical about the health of animals fed hormones and antibiotics choose to eat only organic. And whether you participate in any of these alternatives or not, there’s not much to be said against them. Nothing wrong, after all, with knowing your farmer, or grinding your own burger.

In fact, the very attractiveness of the “better meat” movement, if we can group all of these options under that title, creates its biggest PR problem. The main criticism of the shift toward purer, less processed, more humanely raised meat is that not everyone can enjoy it. Better meat, the argument goes, is inaccessible to the large majority of the population, who simply can’t afford to indulge in $15 pastured chickens or $5 pounds of custom-ground beef.

It’s a well-meant criticism, and true in many ways, but it does ignore one small piece of the puzzle. Even those of modest means can hop off the industrial bandwagon and get fresh, minimally processed meat on the cheap. The cash-strapped consumer can verify personally that the animal she’s getting the meat from is healthy and that its slaughter, cleaning, and preparation meet her requirements. The catch? She has to kill it herself. That’s the way it goes in the self-slaughter business, on display in living color at Jeffries Chicken Farm in Inver Grove Heights.

The name “Jeffries Chicken Farm” is a bit of a misnomer. The enterprise is owned by 78-year-old John Jeffries, but he offers much more than live chickens for sale. The place is pretty much an edible zoo; rabbits and pigeons are available for purchase in addition to the more run-of-the-mill goats, sheep, pigs, and cows. Jeffries does a brisk trade; in one summer week he sells about 2,000 chickens, fifty goats, and five to 10 cows. Winter is a bit slower in the unheated shed where his customers kill and clean their purchases, but a recent Saturday morning was nonetheless bustling, with dozens of people in various stages of progress toward getting their meat home to the oven or freezer. As one family bargained with John over the price of their half-dozen chickens, another peered into the pig pen, debating the relative virtues of the inhabitants and pointing at likely victims, while still another tag-teamed skinning a freshly killed goat.

Over time a rhythm emerged from the initial din of voices, squawks, whining saws, and running water. Each of the largely female contingent of chicken-processing customers found an empty spot on the concrete floor to kill her chickens, wielding in most cases an eight-inch butcher knife to slice back and forth a couple of times through the bent-back throats of the birds. The next step was the scalding bin, into which the dead birds were dunked briefly to loosen their feathers, proceeding afterward to a large cylinder resembling a top-loading clothes washer called the tub or batch picker.

After tossing several chickens at once into the lidless tub picker, the woman in charge would lean forward gingerly to hit the power switch, then leap back a couple of feet to avoid being smacked in the face with any errant feathers that might fly out the top as the birds inside were spun at high speed to remove them. Finally, the mostly naked birds were extracted from the picker, the last few stubborn feathers were pulled off by hand, and the proud owner would head to a stainless steel table to trim off the head and feet and wash and gut the chicken, which finally resembled something you might find in a grocery store. After being tied up with some string the birds were ready to go.

An unspoken order governed the slaughter of the larger animals too; the process just included more players. John’s part-time assistants, David and Lee, brought purchased pigs and goats individually into the alley between the live animal pens and the processing rooms to be killed. Despite the fact that the premise of Jeffries Chicken Farm is self-slaughter, John killed the larger animals himself while the expectant family looked on. He used a rifle; a pig took two shots and a goat one. (The other USDA-accepted method of slaughter for large animals is stunning, followed by throat-slitting and bleeding out. Though John pulled a stun gun out of a drawer in his office to show it to me, it didn’t look much used; rifle shot seemed the preferred method.) Once the animal’s body had stopped reflexively thrashing, David or Lee dragged it into the main room, where the family undertook their role in bleeding it, skinning it, or singeing the hair off if the skin was to be left intact, and gutting and trimming it.

The harsh scene on the slaughterhouse floor would no doubt appall most of us who are used to seeing raw meat only in rectangular encasements of Styrofoam and plastic. The few foodies who follow through on the vision of farm-to-fork food chain transparency usually acquaint themselves with farm animals as they are before slaughter — when they’re picturesquely munching some grass or rooting around in the dirt — and at the dinner table, but nowhere in between. But it doesn’t really matter that we’d all be appalled, because we’re not there to see it anyway. The only people who are there are those who willingly participate in the action, and they largely come from the poorer Hmong, Latino, and Somali communities in the Twin Cities. According to John, they come because they feel the meat is fresher than what they can get at the supermarket, and because slaughtering animals personally is culturally familiar to them. They also clearly come because it’s cheap; one Somali woman I asked admitted that the grocery store was too expensive. Nearly half of them pay for their whole animals with food stamps (John has a machine to process Minnesota’s EBT cards) and the rest pay in cash.

The other noteworthy point about Jeffries’ customers is that they are families, and they don’t leave their kids at home on Saturday mornings to watch cartoons. Boys and girls who couldn’t have been more than five or six years old surveyed the continuous blur of throat-slitting, feather-plucking, and limb-trimming with gazes that could have been bemused or bored, but certainly were neither shocked nor alarmed. Slightly older kids of 12 or 13 played an active role in the proceedings. One such girl planted a foot firmly on the unhinged top of a crate of live chickens to prevent a feathery rebellion while her mother pulled the hapless birds’ necks through holes in the crate to slit their throats. When asked whether she had ever killed the chickens herself, she answered “Yes” with a proud lift of the chin and a smile.

She also said that the 15 chickens inside the crate would feed her 12-person family for a couple of weeks. There’s no question that she’s getting good value for her money by buying those birds from Jeffries. John markets his mature chickens, who on that Saturday morning were mostly spent laying hens from an ex-Amish farmer in Iowa, at 3 for $10. On a recent trip to Cub Foods, a Gold’n Plump all natural (translation: no artificial hormones, which are illegal in US poultry anyway) whole chicken cost $5.99.

Porcine math similarly favors Jeffries. He charges anywhere from $70 to $130 for a whole pig, depending on its size. At Cub, one pork shoulder cost $25 and a set of spare ribs $16. Double those costs and you’re already paying $82 for two shoulders and sets of ribs, and you’re not even getting delicacies like the belly, cheeks, and feet. You’re also missing out on the blood, which some Jeffries customers collect. According to John, the men mix the blood with vodka and drink it to enhance their sexual prowess, but the Cambodian man I saw collecting his pig’s blood in a quart-sized plastic tub resembling a used Cool Whip container couldn’t tell me more than that he consumes it, as he expressed by grasping an imaginary bowl and dipping it toward his mouth.

So, Jeffries Chicken Farm does prove to be a bit of the exception to the rule that fresh, unprocessed meat is available only to those with deep pockets. What Jeffries customers still lack, however, is any guarantee that their animals were raised in a particularly healthy or humane environment. Jeffries doesn’t specialize in meat that’s organic, or antibiotic-free, or rich in omega-3s. He also can’t vouch for the way the animals are treated before they come to him; he buys his chickens from a wide variety of area farmers, and his large animals from all and sundry at auction. Still, his customers can at least monitor the visible signs of good health in their animals: that they are alert, bright-eyed, unblemished, and able to walk around. That’s a lot more transparency than any trip to Cub will give them.

And that’s the business opportunity that glinted in John Jeffries’ eyes 20 years ago when he founded Jeffries Chicken Farm after being a livestock trader for decades. But, he says, at nearly 80 years old, he hasn’t stayed in it for the money, nor because of any particular affinity for chickens. The reason he still gets up to meet his first customers at 6:30am, even on the weekends, is that he loves people. He loves bargaining with them, joking with them, patting their kids on the head. As he says, “It’s not work when you like it.”

Jeffries Chicken Farm

3250 105th St

Inver Grove Heights, MN 55077

651.455.3974

HOURS: Vary. Typically Jeffries is securing animals Monday through Wednesday, so the farm only opens if he happens to be around. Thursday through Sunday they open around 6:30am and close when business slows down. On the weekends that might be soon after noon, but on weekdays they do stay open for customers coming in after work.

Thanks for this great article. I applaud this company for providing an option for people to slaughter their own animals, if that is something that is important to them, while offering a lower cost option than the standard supermarket. The process of slaughtering an animal is not pretty, nor should it be glossed over. There’s no magical, clean process that transforms frolicking animals into sterile, packaged cuts of meat.

What we need is the Met Council to push for Cities to provide tax and other incentives for these fringe metro farms to stay in operation and new ones to proliferate.

Too often prop taxes and assessments are used to push these long term operations out and replaced with what appears to be higher grossing prop tax developments. I can think of dozens of farms on the fringes of the metro at risk at the moment. Often when the elder owners get too old the crush of inheritance tax and green acres accumulated back tax take these operations out of the food system as the children or new buyers cannot swallow the huge one time expense.

I have felt this topic is ripe for an in depth documentary or similar media attention to bring this issue to the table.

We need to look at these last farms as a precious resource not as a source of more development land for just another McMansion.

What a fascinating story. Thanks Angelique and Kate. This farm is clearly a huge asset to the Twin Cities.

Thank you for sharing this article. I will let my friends know about Jeffries farm. I wonder if Jeffery and his team will do the all the work if people are willing to pay extra.

People from Nepal celebrate their biggest festival called Dashain in October and that’s when they consume the most meat. Mountain goats are brought in humongous numbers in huge fields where people flock to buy their goats and slaughter them at home. While they cannot do that here, what they do is two or more families (usually friends) chip in to share one goat then they order the goat at the Slaughter house in St. Paul owned by the Hmong people. The people at the slaughter house do everything (including cutting into pieces) which makes it easy for the customers. This way the Meat is fresh and cheaper too.

Is there a farm anywhere near the twin cities that one can purchase and slaughter a chicken or other animals that are free ranging or organic?

wow, this is very interesting. I miss the days when I sat with my grandparents and helped clean chickens and ducks. it was usually done 2-3 times a summer. I grew up on a farm in SoDak. I wonder if I could visit the farm and pitch in. I’m sure I’d buy a few chickens of my own. we also had pigs, and my dad still raises cattle and goats on the family farm, but we always used the local butcher shop for the processing of those.

Brava for this careful and thoughtful post. As you say, there’s a lot of willful blindness among foodies about the process that transforms an animal into food. If we’re going to eat meat, we ought to be willing to be witnesses all the way through.

Awesome story! I’ve been wanting something like this. I grew up in rural WI and have butchered chickens and deer several times. I think I’m going to go and get a pig and a lamb. :)

Just received this via email — may be of interest. “Rickie Lee on 2/8/20 1 pm asked where to get free-ranging chickens for slaughter. We have them. Please, post for your readers. Our birds have been pastured, fed local grains, organic feed and 16% layer commercial feed. Rosters for sale $5-10.

Garry Fay

Freedom Farm

1531 Andersen Socut Camp Road

Houlton WI 54082

three miles from Stillwater MN”

We have free range chickens including heritage breeds in the fall right here in Northfield Minnesota. Our farm is a network of a growing system of regional small farm enterprises designed to produce high quality poultry in a well developed system for full integration of the ecology and farmers and consumers. Check this recent article about us: http://www.startribune.com/lifestyle/82429832.html

Also check our weblog at http://www.ruralec.com to stay tuned to many other opportunities. A facebook link to our cooperative of local farmers is also available at the site.

do you sell chinkin feet and for how much

My parents had just come back from Jeffries Chicken Farm and had a bad encounter with John, the owner there. My mom asked politely for him to change the hot water from the tub, because a family had just killed a sheep and dipped it in the water to clean it. He refused to do it and then said he would, but he came back and said he wouldn’t. So my mom asked him to refund the money back into my mom’s card, because the pig has not been killed yet. He said that since the pig has been purchased, he will not refund the money back and that they’ll have to kill the pig. The argument went on for a while and he said to my younger brother that they were people with no country and there are no other pigs that is why they came to him. This upset my younger brother, so he demanded that John refund the money or he is going to call the cops. John then refunded the money and my parents left. This is a prejudice place, my mom has said, he has said bad things to her in the past also. This time someone who knows english well is with her, so when the cops were going to get involved, he took into action quick with returning the money. DO NOT GO, OR YOU WILL GET THE SAME EXPERIENCE……!!

DON’T WORRY, THIS WILL BE SENT TO ALL MY FRIENDS VIA FACEBOOK, WHO SLAUGHTER ANIMAL TO SAVE A LITTLE. IN THE END, WE WILL SEE WHERE JOHN FROM JEFFRIES FARM WILL BE HEADING. OUT OF BUSINESS, CAN WE ALL SAY THAT!!

very good place….. nice people work there

Hi everyone.I want to open a live chickens market in Northern California. Anyone out there know the Website of wholesalers.Thx

Is there a team that does the slaughtering for the customer