“In the isolated mountain villages of their Laotian homeland, cooking was… the stuff of tradition, not the written word. Good Hmong cooks learned from their elders which ingredients to use, and how much of each, by sight, feel, and taste. Recipes were never written down and followed ‘to the letter.’ Cooking, like other Hmong arts and crafts, came ‘from the heart.'”

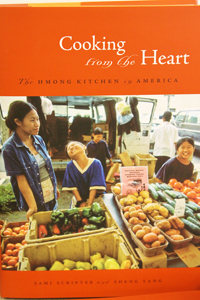

(From Cooking from the Heart: The Hmong Kitchen in America by Sami Scripter and Sheng Yang, published this month by the University of Minnesota Press ($29.95; 248 pages, hardcover with color photos, available at Hmong ABC Bookstore at 298 University Ave. W in St. Paul).

Sheng Yang, and her parents and four siblings, immigrated to the United States — first to Kentucky, then Oklahoma, and then, Oregon — in 1979, when she was nine. Sami Scripter, married and tending to her growing family, was Sheng’s neighbor in Portland, OR. Sami worked as an educator at Sheng’s elementary school. Speaking to a small audience at the Hmong Cultural Center in St. Paul on Thursday, Scripter recalls, “One year you didn’t know what Hmong was, and the next year a quarter of the children in school were Hmong.”

Yang says that over the years their “two families have become almost one.” Scripter adds, “We got to know each other the way neighbors know each other.” They gardened together in the Scripter’s backyard using seeds Sheng’s mother had carried from Laos and Thailand. Sami taught Sheng and her mother how to preserve raspberry jam.

As a sixth grader, to improve her English, Sheng lived with the Scripters, rooming with Sami’s daughter, Emily, in a bunk bed Don Scripter built for the two girls. “Sami learned to cook rice the Hmong way using an hourglass-shaped pot and woven basket steamer, and Sheng learned how to make… meatloaf, baked potatoes, and peach pie,” the authors write.

Out of their friendship and years of cooking together and jotting down ingredients grew Cooking from the Heart, which is as much a “celebration of Hmong culture as it is lived in the United States” as it is a cookbook, Yang says. “We wanted to remember who we are… to store the heritage and cooking and pass it down to our children to keep and treasure for years to come.” Scripter adds: “There are many ways of remembering: the Hmong oral tradition is one way; the paj ntaub [Hmong embroidery, pronounced “pa dao”] that women sew is another way. And a cookbook is a way.”

In their book, Scripter and Yang touch on eating etiquette and table settings; herbal medicine and healing traditions; and weddings, New Year’s, and funeral customs, and the role food plays in each. Of funerals, the authors write: “The haunting notes of a Hmong bamboo pipe, called a qeej [pronounced keel, pulling your lips tight and speaking almost from your throat], and the rhythmic tum, tum, tum of a special wooden drum constructed exclusively for the service pervade the atmosphere of a traditional funeral.” (Txu Zong Yang plays the qeej and performs the complex dance movements in the photo to the right).

“Three times a day a gong signals meals for all attendees. The deceased is symbolically fed. Then everyone attending the funeral is also fed… It is common for a family to have one or more cows or buffalo butchered and cooked each day to feed the crowd. Cauldrons of boiling meat… are prepared. Mountains of rice are steamed… As with many rituals and events, food is an essential component contributing to the solidarity of Hmong people.” The authors devote an entire chapter, “Cooking for a Crowd,” to dishes commonly served at Hmong gatherings.

The book is sprinkled with Hmong poetry and essays, such as May Lee-Yang’s “The Year My Family Decided Not to Have Papaya Salad and Egg Rolls for Thanksgiving,” that convey the joys and challenges of growing up Hmong in America.

One side-bar, Ka’s Journal, tells the story of a Hmong woman who, unbeknownst to her family, painstakingly recorded the events of her life, including drawings of Hmong cooking tools, in a spiral-bound notebook she kept in a basket under her bed, wrapped in a skirt. Her children discovered Ka’s journal only after her funeral.

Rather than try to document Hmong cuisine in general, Scripter and Yang focused on “what individual Hmong cooks do,” coaxing recipes out of family and Hmong cooks around the US. Recipes include Saly’s (Yang’s mother-in-law) Rice and Corn Pancakes; Der’s (Yang’s sister) Egg and Cucumber Salad; and Chee Vang’s (a woman who lives in Denver, CO) Stuffed Chicken Wings.

“We wanted to write about Hmong cooking everywhere,” says Scripter. “We cooked in other people’s homes.” The dish that everyone loves, in spite the “startling array of differences” in the ways it’s prepared, says Scripter, is Chicken Curry Noodle Soup or Khaub Poob (pronounced kah-poong). “Some put quail eggs in it. Some make it with garlic, some without… It’s all very good.”

The book includes an extensive discussion of cooking tools, packaged ingredients, and vegetables and herbs used in both cooking and healing. Rather than trying to gloss over ingredients that may seem out of favor, such as MSG, or unfamiliar to non-Hmong or Hmong who have grown up in America, Scripter and Yang take the challenge head-on. Of Traditional Beef Soup, “cow-poo soup,” made of beef stomach, intestines, and organ meat, they write: “Contradicting its name, the soup is made of healthy ingredients and is very nutritious. However, this dish may not be for people who are one or more generations away from having to eat whatever is available in order to live.”

At the book signing, Scripter and Yang elaborated on what distinguishes Hmong cooking from other Southeast Asian cuisines. The flavorful, fragrant rice, which requires two hours to cook, is one distinction. Yang tells how, after she was married 25 years ago, “I didn’t make rice for three months.” She knew her father-in-law wanted the rice juice and the rice at the same time. “I knew he would ask: ‘Who made the rice tonight?’ And if it was good, it would be the biggest compliment ever; but if it was bad…”

It is also “very Hmong to cook with blossoms,” including squash and yucca blossoms. The unusual herbs and vegetables, some bitter, particularly the medicinal ones, picked only at their peak, is another distinction. Cooking with shoots is a part of the cuisine, as well. Scripter tells the story of a hike she took with Yang’s family near Portland. When Scripter realized Yang’s mother was no longer with them and inquired about her whereabouts, Yang’s sister replied that her mother was “down there in the pea vines, picking the ends off.” They ate those pea shoots steamed for dinner that night.

The authors also provide insight into how Hmong are adapting in America, including profiles of Chuedang Vue and his wife, Gao Youa, who opened Rice Palace Restaurant in a former bowling alley in Milwaukee, WI, and of cousins Fhoua Chee Yang and Kao Yee Xiong of St. Paul’s Cakes by Fhoua. Yang and Xiong, despite teasing from their elders who urged them to get married young and have children, broke from the Hmong tradition and postponed starting their families, and instead attended college, and, for Fhoua, trained at the Minneapolis/St. Paul Cordon Bleu Patisserie and Baking School, so they could start their own bakery. Scripter says people who’ve read the book tell her: “‘I cried when I read about Fhoua and her bakery’… The book is about Hmong following their hearts and dreams, contributing to their own culture and the greater culture.”

Cooking from the Heart, 30 years in the dreaming, was written from the heart.

***

THE RECIPES

I tried several recipes from the book, Beef Noodle Soup (pho, pictured above), Sheng’s Green Papaya Salad (which I made with carrots as Sheng first did for the Scripters: the recipe is included here), Fresh Chicken with Hmong Herbs (Soup for New Mothers), and Chicken Larb [pronounced “lob”] (Laotian Chicken and Herb Salad). (Recipes for the Soup for New Mothers and Larb appear below).

My husband, who, at my urging ( “The book says the men prepare the larb,” I said) chopped the chicken for the larb, enjoyed the dish so much that he declared the dish–which is served at room temperature– our “go to” for picnics and potlucks this summer.

I feared my biggest challenge would be acquiring the unfamiliar ingredients — pastes, spice packets, Hmong herbs, and galanga root — but trips to the International Market Place at 217 Como Ave. in St. Paul and Dragon Star at 633 Minnehaha Ave. W in St. Paul helped me over that hurdle. Though the book provides outstanding context and ingredient descriptions, I found myself occasionally puzzling over an unfamiliar recipe or technique. The pho recipe calls for “1 whole yellow onion.” The authors say, “Peel the papery layer off of the onion and add the onion to the pot.” No dicing, slicing, chopping, or quartering? I re-read the recipe, looking for guidance, then called my husband into the kitchen. “Am I supposed to add this onion in whole?” I asked, shoving the book into his hand. I was also puzzled about what to do with the oxtail meat that the authors tell you to remove from the broth and refrigerate. I scoured the recipe, trying to figure out at which point I should add the meat back in. Ultimately, I decided to put my faith in the authors: I put the onion in whole, and left the oxtail meat in the fridge.

Later, Scripter confirmed, “Yes, you add the onion whole. Both the onion and the oxtails are used simply to make a rich, flavorful broth, but neither appear in the final soup. Hmong people would nibble the cooked meat off of the bones (they waste nothing) but not as part of the soup, so we suggested refrigerating them. The solids referred to are the meat, bones, ginger root, star anise, and gritty stuff from the meat and bones. What you want in the end is a rich, relatively clear broth. Some people char the onion before adding it to the soup. That adds to the flavor, but the Hmong people who made the soup for us did not char the onion, and Sheng does not, so we left it as it is. (I like the charred flavor, which is a Vietnamese touch.) The beef in the finished soup includes thinly sliced beef tenderloin that is cooked by the hot broth that is spooned over it and also store-bought beef meat balls.”

One additional tip I will add for anyone who tries the pho: buy the best meatballs you can, not the ones that are on sale, as I did.

For the most part, I found that the steps in the recipes are meant to be taken literally and that if the authors don’t mention a particular step, such chopping an onion or returning meat solids to the broth, then you aren’t intended to do it.

My challenge with the chicken soup for new mothers was not, as I expected, finding the herb bouquet, Tshuaj Rau Qaib (pronounced chua chao kai), which I purchased from a vendor at the International Market in St. Paul by asking around for the “herbs for the chicken soup for new mothers,” but rather figuring out to proceed with the very basic step of adding “several sprigs of each herb” to the pot of water. Realizing I had no idea what was in the herb bouquet, I untangled the herbs and separated them into piles: the slender grass-looking ones, the broad purple leafy ones, the jagged ones. Then I pondered what constitutes a sprig of grass. I would know what to do if I had a handful of thyme, but how much duck-feet herb is enough? Moving onto the chicken, which I’d chopped into 16 pieces, I wasn’t sure whether to remove the skin.

Scripter clarified for me: “For a truly traditional soup, the skin is left on as well as the head and feet. Of course the chicken needs to be well cleaned. Cook with the lid off, and make sure the pieces of chicken are small enough to be cooked through in the time allotted, or extend the cooking time a little. The times I made this soup I used herbs from a Hmong friend’s garden. They are pictured on page 97. We were not able to find English names for some of them. Of those herbs, the only ones I have found in Asian markets are the Vietnamese coriander, the betel leaf, culantro (saw leaf herb), and slippery vegetable. All three of those have rather strong flavors… A Hmong cook would add about 2 cups of loosely packed herbs to the soup. To boost the flavor, try cooking the lemongrass in the water for a while before adding the chicken. However, this soup does not have a strong flavor. Although it is rather bland, the subtle flavors are very ‘Hmong.'”

By the time I’d read through the entire book, trying recipes, and peppering the authors with questions as I went, I realized what I really needed to do was add ingredients to taste as the authors advise throughout the book. If I wanted more, add more. If I wanted to skim the soup, skim the soup. All I had to do was follow my heart.

The below recipes have been excerpted from “Cooking from the Heart.”

Chicken Larb (Laotian Chicken and Herb Salad) Laj Nqaij Qaib

Makes 8 servings

Light, healthy, and full of flavor — nothing can beat chicken larb for a simple but elegant meal with friends on a warm summer evening. This version is easy to make and can be handily be halved or doubled, and the ingredients can be found in almost any grocery store.

Use only fresh, blemish-free herbs. Chop and slice them by hand, because a food processor will bruise them. Loosely pack the herbs into the measuring cup. Although you can use ground chicken or turkey, chopping the meat yourself gives the dish a finer, more desirable texture.

2 whole boneless chicken breasts or 3 lbs ground chicken or turkey

Juice of 2 large limes, plus 1 lime for garnish

2 tbsp rice wine

2 tsp minced fresh ginger (for a more traditional taste, substitute galanga)

1 stalk minced lemongrass, tough outer leaves, root, and top several inches removed before mincing

3 tsp grated lemon peel

2 small hot chili peppers, minced, or 1 tsp crushed chili flakes

1 clove garlic, minced

1 tbsp fish sauce

1 ½ tsp salt

½ tsp white pepper

3 tbsp Toasted Sticky Rice Flour

1 chicken bouillon cube

1 heaping cup chopped fresh mint

1 heaping cup chopped cilantro

1 bunch of green onions, green part chopped, white part sliced diagonally

½ c chopped Thai basil

1 large head leaf lettuce (16 leaves, for wrappers)

Several additional stems of mint and cilantro, for garnish

On a large, clean chopping board, chop the chicken with a heavy knife or cleaver. As you chop the chicken, fold it over on itself. Continue to fold and chop until the meat is very finely chopped. Put the meat in a large bowl and squeeze the lime juice over it. Add the rice wine. Cook the chicken mixture in a nonstick skillet (don’t use any oil) over medium-high heat, tossing and stirring constantly just until the meat turns white. Return the mixture with any accumulated juice to the bowl and allow it to cool to room temperature. While the chicken cools, prepare the fresh herbs. Add the ginger (or galanga), lemongrass, lemon peel, chili peppers (or crushed chili flakes), garlic, fish sauce, salt, white pepper, and rice flour to the cooler mixture. Break apart the chicken bouillon cube and sprinkle it on top. Toss the ingredients together until they are well mixed. Then add the mint, cilantro, green onions, and Thai basil. Gently toss everything together. Break lettuce leaves away from the head, and wash and dry them.

Fresh Chicken with Hmong Herbs (Soup for New Mothers)

Nqaij Qaib Hau Xyaw Tshuaj

Makes 1 pot of soup

1 whole fresh chicken (the kind purchased from a Hmong market or farm)

10 c water

1 stalk lemongrass, tough outer leaves and root removed

1 tbsp salt, or to taste

½ tsp black pepper

Hmong herbs

Each cook cites favorite herbs, often including hmab ntsha ntsuab (slipper vegetable), koj liab (angelica, sometimes called duck-feet herb), ntiv (sweet fern), pawj qaib (sweet flag), tseej ntug (common dayflower), and ncaug txhav and tshab xyoob (for which no English translations are available).

Clean and chop up the chicken into about 16 pieces. Refrigerate the giblets for other uses. Pick or buy the herbs shortly before using, and wash them carefully. Several sprigs of each herb is the customary amount. In a medium-sized pot, bring the water back to a boil and add the chicken pieces. Boil 15 minutes (do not overcook the chicken). Add the herbs and cook a few more minutes. Remove the lemongrass and serve with rice.

RESOURCES:

“A Day in the Kitchen of a Hmong Family,” with recipes, resources for shopping for equipment, produce, and groceries, and information about Hmong Markets and restaurants.

Cakes by Fhoua

Cakes by Fhoua is currently searching for a kitchen with a store-front, but is still available to take orders for their cookies and cakes, inspired by Hmong paj ntaub patterns

651.644.1331

Rice Palace Asian Cuisine

3730 West National Ave.

Milwaukee, WI 53215

414.383.3156

International Market Place

217 Como Ave. (near Marion St.)

St. Paul, MN 55103

651.487.3700

Dragon Star Oriental Foods

633 Minnehaha Ave. W

St. Paul, MN 55104

651.488.2567

Purchase the book:

Hmong ABC Bookstore

298 University Ave. West

St. Paul, MN 55103

651.293.0019

Wow Lori, another impressive piece for this site- you are raising the bar! Thanks- so, what do they say about msg? Any explanation of how something that seems to come from a factory is in traditional foods?

I agree with Faith: this is another excellent article. Keep ’em coming!

i sent this article to Lynne Rosato Kasper’s show, turns out they are being interviewed for a show to broadcast soon… great!

That is great! Lynne Rossetto Kasper wrote a blurb for the book jacket saying that “Any serious collector of food books… will want this book.”

Faith, I don’t recall that the authors went into detail about the origins of MSG usage, except that they said these are recipes from actual Hmong people living in America. Some use MSG, some do not, and where a recipe in the book calls for MSG, it is always marked optional.

What an amazing amount of work this review had to be but the beautiful pictures made me want to try everything and the recipes made me hungry and I just finished eating!

Excellent review, Lori. I think your husband is right about the “go to” for potlucks and family events.

I picked up the book today and it is wonderful (had lots of time to read it waiting at Burger Jones, first for a seat, then for the food.) A good friend of the family is from Laos and so I recognize so many of the dishes as ones we have eaten at her house and wedding. I’m excited to make them myself.

And, she is a big MSG user. Except she doesn’t call it MSG, she calls it “salt.”

My friend Yee and I swap foods together. Las t time I saw her she brought me some lemon grass and a “hmong pumpkin”. The pumpkin is about 5 pounds, light and medium green with cream colored spots running down the ribs of the pumpkin. Can anyone tell me how to prepare it?

Alan, in “Cooking from the Heart” the authors say that “Asian pumpkins have gray-green skin and bright orange flesh. They are similar to pumpkins, which can serve as a substitute.” The book has a recipe “Smoked Pork and Young Asian Pumpkin,” which appears to be a soup. Peel and de-seed the pumpkin, then cut it into bite-sized pieces. Cut a pound of smoked pork into bite-sized pieces. Bring 5 c. of water, 1 tsp salt, and a stalk of lemongrass (smashed) to a boil, then add pork and boil until pork is almost cooked (10-15 mins). Add pumpkin cubes. Boil until the pumpkin is soft (but not mushy). They also have you add a small bunch of de-veined pumpkin vines (cut into 6-inch lengths) along with the cubed pumpkin. (Serves 4, in individual soup bowls.) Did your friend give you any pumpkin vines?

Alan, an often dish that my mom cooks when Fall rolls around is simply just cutting the “Hmong pumpkins” into smaller pieces and then boiling them until they are soft (and not mushy). It’s kind of like a soup, I suppose. It helps relax and cleanse your diet a bit. My mom sometimes add a bit of sugar into it to give it a sweet taste. We usually pour a bit over warm soft rice in a bowl and eat it (either with another side dish or not). My mom usually collects a lot once Fall comes around, but this year, we’re already out! And I’m hungry for some! The dish above that Lori Writer has shared in her comment also seems like a great dish to try out with “Hmong pumpkins”…I should give that a try too one day! (I’m now living on my own, and it’s so hard finding all these veggies and ingredients too!) Good luck!