Like most people, I’ve been to plenty of weddings. And also like most people, I’ve developed personal preferences about who I’d like to be stuck at a table with. Last on the list, below even grouchy exurban MAGA boomers, are people with PhDs in English or Philosophy. Without fail, when the conversation turns to work, descriptions of their projects turn into an opaque tornado of academic jargon so nonsensical that I eventually slink quietly away to the bar, never to return.

Far preferable: scientists and engineers. Despite doing work that my tiny, humanities-addled brain can barely fathom, they strain heroically to render their projects comprehensible. They use metaphor, simplification, context, and clear communication to help me understand how they’re mapping the speech center of the brain, or engineering new strains of barley, or creating more effectively articulated joints for robots. Even when I can’t really grasp what they’re talking about, I appreciate the effort to bridge the gap.

I’ve read loads of cookbooks from pedigreed chefs and decorated restaurants, and most of them talk to their readers like professors who have spent 40 years studying one particularly obscure collection of short stories by James Joyce. They work so hard to convey that what they’re doing is difficult, expensive, and failure-prone that they make the actual conveyance of knowledge almost impossible. The majority of upscale cookbooks I’ve read are shiny, lovely, mostly unusable doorstops.

Chef Gavin Kaysen’s new, self-published debut cookbook At Home is a happy exception to that rule. Kaysen certainly has a pedigree (Spoon and Stable is a rock of fine dining that trendier spots around here generally lap briefly against before retreating back into the surf), but like an earnest robotics engineer, he labors heroically in “At Home” to write clearly and help the home chef achieve a good result.

The book has a reasonably small number of recipes that are helpfully sorted by season. The book is curated to include dishes that people can joyfully recognize (coq au vin, Swedish meatballs, or croque madame for example) and while there are plenty of prestige picks (classic French cassoulet, anybody?) the key organizing principle is clearly “stuff that people might actually want to make and eat.” There aren’t a lot of off-putting restaurant curiosities, and most of the sub-recipes and sauces seem intrinsic and worthwhile, not maddening and punitive.

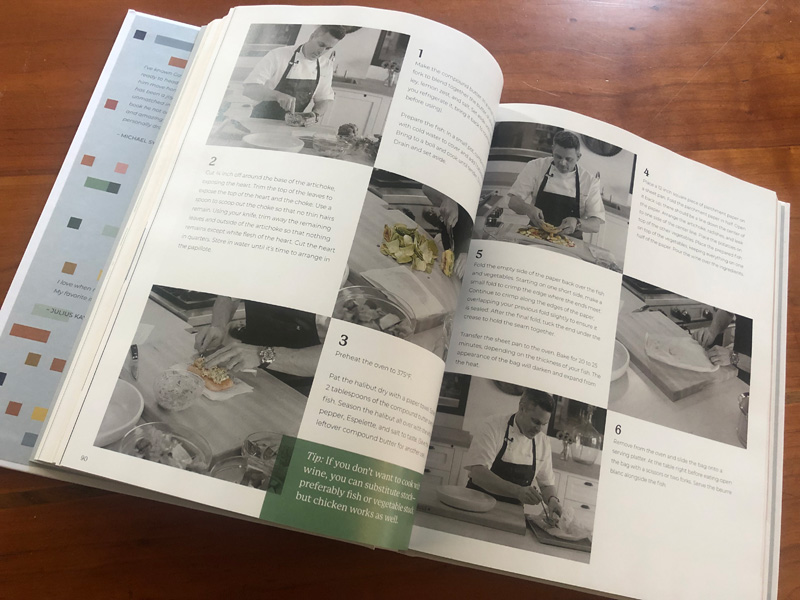

Clever use of photography – in particular, photos series that helpfully lay out the various steps of what could otherwise be a challenging dish – makes “At Home” still more accessible. In short: yes, Kaysen is often trying to teach you how to do something moderately challenging or even quite difficult, but he’s legitimately doing his best to show you how to pull it off. He takes his time, and he walks you through the steps.

To put the book through its paces, I tackled a recipe that was challenging enough without demanding a weekend of work: Pappardelle Pasta with Pork Ragu. There were a couple of snafus: I made an insufficiently large well in my mound of flour while making the pasta, creating liquid egg Mount Vesuvius, and I didn’t get much of a fond in my ragu because I reflexively (and incorrectly) seared the ground pork in olive oil rather than in a bare pan. But the final result was something that won legitimate raves from my jaded and praise-stingy family. The ragu was truly rich, balanced, and deeply flavored, and the noodles were springy, tender, and a perfect match with the sauce.

(Plus, I got to use our 118-year-old noodle rack, which is always a treat.)

There are parts of the recipe that were too fussy for me, personally, but they were also easy to discard. Elaborate directions for how to fold and cut sheets of noodles so that they’re uniform in size and appearance aren’t my bag – I’m OK with ragged-looking fresh pasta, because it still tastes delicious and, in my opinion, looks charming in that state as well.

And while the recipe instructed me to mince the garlic before it was pulverized in a food processor, that to me seemed like working harder rather than smarter, and, as expected, the food processor did a fine job of blitzing that allium to a paste without any additional busywork on my part.

These are quibbles, though – Kaysen’s a pro, and he wants you to be able to at least strain toward his level. I most certainly am not, and I’m comfortable being informal in my home kitchen. And ultimately, the recipe turned out well: odds of me making it again are close to 100 percent, and At Home is going into the prime pantry real estate rather than the basement Siberia that is home to the many dozens of cookbooks I haven’t yet sold but don’t plan to use any time soon.

For breakfast this morning, I tried another recipe, this one much simpler: a classic French omelet. I don’t have a good track record with omelets – mine tend to be brownish, mottled, and uneven at best. But because At Home sets clear expectations (keep the eggs moving until just before they’re set, shoot for an omelet that doesn’t even have a spot of brown), I was able to get my head in the game and produce a tasty, reasonably neat-looking specimen with minimal effort.

From curation to illustration to writing, At Home is that rarest of cookbooks: one you’re likely to use frequently and without concern about its recipes flopping. It’s a real celebration of cooking well for your family, and it’s a confirmation that if you’re trying to explain something complicated, look for language that’s correspondingly simple.

“At Home” by Gavin Kaysen, Spoon Thief Publishing, $35, 265 pages