Heavy Table published a long retrospective interview with restaurateur and “Food Guy” Tobie Nidetz this January in our Tap newsletter. This week, he passed away after a long illness.

If you cover a region for long enough, you start to meet the players who make things tick behind the scenes. After a few years of digging around the world of Upper Midwestern food, we started bumping into chef and restaurant consultant Tobie Nidetz again and again, and we found him to be as thoughtful as he was omnipresent.

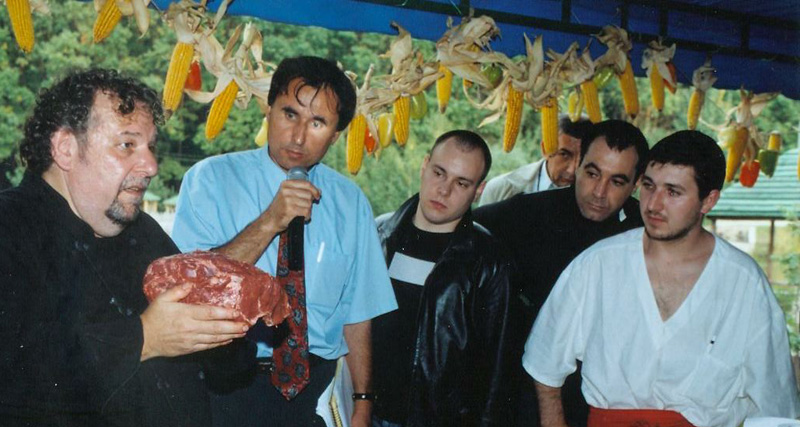

Nidetz got his start with the now-sprawling Lettuce Entertain You restaurant group in Chicago (pictured above, with football), and has consulted on or worked for properties as diverse as the St. Paul Grill, Ike’s, Cocolezzone, Green Mill, Cara Irish Pubs, CoV Edina, and the Sample Room. He also operated a couple restaurants of his own, both in Minneapolis: Tobie’s Tavern in the early ’90s, and Prairie Dogs in the early teens.

Nidetz is now battling congestive heart failure (it’s “a forever sort of thing,” he notes) and looks unlikely to return to the grueling hours typical of a chef or restaurateur. But he’s still producing an ambitious podcast about the restaurant world and he’s got about 50 years of stories, so we reached out and asked him to tell us about his life in food thus far.

HEAVY TABLE: Take us back to Chicago, where it all got going for you.

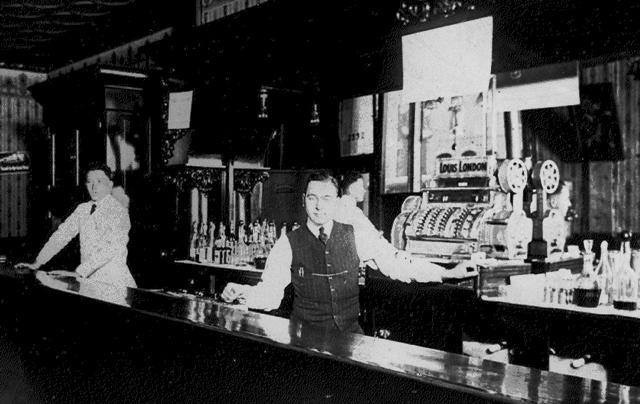

TOBIE NIDETZ: I sent you the photo of my grandfather in his bar in 1914 [below]. I wasn’t around then, but that’s kind of where the family business started.

And then in 1960 my dad bought a little broasted chicken and rib joint in suburban Chicago. Of course I had to be there every night, my mother would pick me up after school and take me there and I’d be filling coleslaw cups and breading chicken.

All through high school, though, I kept away from the restaurant business. I was really anxious to get into theater and film. But when NYU’s film school rejected me, I had to make a decision: am I going to keep applying to film schools or become a chef like everybody was telling me to do, because I was so interested in cooking.

HT: So your family sort of pushed you into the industry?

NIDETZ: They were happy to let me do whatever I wanted to do. But because of their insight into the restaurant and bar business, they knew I’d be good at it.

My girlfriend’s mother found a chef who would take me on and when I was 18 I apprenticed with John Snowden [at Dumas Pere l’Ecole de la Cuisine Francaise].

His background is very interesting. He’s an African-American – born in Mexico to an African-American woman – and at the age of 14, left Mexico to go to Europe to learn how to cook. He wound up in the kitchen of Fernand Point where Paul Bocuse and the Troisgros Brothers all ended up, and did his real education at the Swiss Hotel [Management] School. And then he came back to the United States in the ’50s and no one would hire him because he was black.

HT: So where did he cook…? How’d he become this well-known figure in Chicago culinary circles?

NIDETZ: He got a job with a railroad, and he cooked with them for several years. And he opened a couple restaurants without health permits, and then settled into doing a cooking school, and that’s where I met him.

As his apprentice, I would get there at 5:30 or 6 in the morning, when I could remember to get up that early. And I’d prepare the croissants because he’d have croissants in the little bakery case up front. Then during the class, I’d cook along with everybody, and then after class I’d clean everything up.

And between classes I’d take care of his two Afghan hounds, feeding them their special diet and taking them out for walks, which is an experience everybody has to do, especially if you’re a dog lover. Afghan hounds are runners. They don’t want to walk, they want to run. So I learned how to get them under control, at least.

HT: Did you pick up any life lessons from Snowden that you carried with you?

NIDETZ: Don’t stay up too late at night, so you can get up at 5 o’clock in the morning. And understand where your education is coming from. The heritage of what I was getting from John is something you can take all the way back to Alexandre Dumas, [Marie-Antoine] Carême, and [Auguste] Escoffier.

That background made me want to do fine dining at the beginning. But I was being asked to take on jobs at restaurants that were casual dining, although we didn’t really know what that was in the early ’70s – and use my techniques and knowledge I gained in my apprenticeship to … I don’t want to say ‘bring it down a level,’ but bring it to a wider audience to appreciate it.

HT: That seems like a pretty significant theme, in terms of the rest of your life’s work.

NIDETZ: I wasn’t thinking about it at the time. These restaurant owners were asking me to do stuff… I created my first restaurant menu when I was 24, in a restaurant called Tango, that I totally … fucked up. There was no way I was ready to run a kitchen. I could create food for a menu, but that was as far as it got.

HT: What was the disconnect? What couldn’t you do?

NIDETZ: I wasn’t able to manage the people, I wasn’t able to buy the food properly so it was in a good cost range. Actually I got so tired one night that I dreamt I had placed the produce order. I went to work the next day and the produce wasn’t coming in, so I called them and they said: ‘Well, you never placed an order.’

That was about the peak of my downfall. I actually had to walk out on a busy Saturday night because it just became too much.

HT: You eventually moved from Tango to the then-small Lettuce Entertain You group, which has since become a colossus. How’d that happen?

NIDETZ: Rich [Melman] was looking for somebody who could help create food for menus, and he’d send me off to restaurants to taste things, and I’d come back and make them for him. And I’d make new items for the two existing restaurants and for the other four restaurants I’d create the menus as well.

They called me the executive chef for Lettuce Entertain You when Lettuce got formed. The business side I’d picked up along the way, there were some great people at Lettuce who taught me how to manage a kitchen and that was priceless, that sort of education.

HT: What kind of a chef and manager were you at that point?

NIDETZ: I had this huge, huge problem of perfection. There was good and bad, but only perfection mattered. And I kept looking for that in how I was training people, for them to return dishes to me perfectly like I showed them. Or to set up a station correctly, or even just to be on work on time. I was looking for that perfection.

When I got to Minnesota, I was known for being able to throw a rye bread, spiral, for 30 or 40 feet. Because if it was made wrong, I’d throw it away. I’d yell at everybody.

I’d do that back at Lettuce… It kind of worked for a while. People kind of got into line, really quickly. But it became too much, this sort of pressure I’d put on myself, more than anybody else, was something I had to learn how to stop doing.

HT: What brought you to the Twin Cities?

NIDETZ: 1979 was when I met the Webb brothers, Rick and Dave.

They were just building Winfield Potters at the time, and they wanted me to create a menu based on the kitchen they were building, because they’d spent so much money on it. They just kept asking me to come back and stay.

I stayed here for six or seven years, and eventually I started moving away from what they were doing, and I was having these emotional bouts with David. And eventually I started doing consulting, and I moved back to Chicago because a lot of my consulting was being done down there.

I came back up here in ’90, because Rick had asked me to be the GM for American Cafe and Coco’s [Cocolezzone], which were the two restaurants next to the nightclub [Rupert’s]. So I said sure, and of course there was a woman involved. There’s always a woman involved.

HT: What was the Minneapolis-St. Paul scene like when you first moved here?

NIDETZ: Lexington was open and doing very well. Charlie’s [Exceptionale] was still open, actually. The chefs were all these Swiss- and German-trained executive chefs. But there was really nobody who came from the CIA or anyplace else, like Johnson & Wales.

The food was either white tablecloth on one end or Perkins on the other end, with nothing in between. The effort that we put into Lettuce in the beginning was to build this new casual atmosphere for restaurants. And that’s what the Webbs wanted for Winfield Potters, was that same casual atmosphere.

HT: So, with the job of restaurant consultant – what are you actually doing? What expertise are people paying you for?

NIDETZ: Mainly it was focused around the menu. I’d do recipe creation, and menu design, and kitchen design mostly. But I got involved in training front of house staff, as well. [It used to be that] the definition of “restaurant consultant” was “a chef who is between jobs.” But I was more than that, because consulting was my job.

I described it as anything the restaurant owner couldn’t do or didn’t want to do.

HT: What was the story with Tobie’s Tavern, from ’93-97?

NIDETZ: It was at First [Avenue] and Sixth [Street], right across from the Target Center. At the time, it was mostly an empty lot because the old Shubert Theater had been moved by then.

There was a room upstairs almost the size of the building that I could use for music or parties or whatever. And there were two kitchens, there was a kitchen upstairs I could use for prep and a kitchen downstairs I could use for service. And an ancient freight elevator that brought everything up and down. I was constantly in fear I’d send somebody up to get something and they’d never come down.

The concept was supper club. I thought it was a great spot, and people today still tell me it was a great spot. But the two years I was open we had road construction both summers, so we were screwed. After three years of operation we were starting to turn it into a thing, when the city came in with eminent domain and took our building. There’s a spot inside Kieran’s – there’s a bar where my bar used to be.

HT: What were the big sellers?

NIDETZ: We had a chicken caesar – and we made the dressing scratch for every salad by the way – and on top of it was chicken we had pre-cooked and coated with a parmesan cheese and butter combo that would turn into a crust when we reheated the chicken. That did very well.

Steaks – I had the filet with the peppercorn sauce and a sirloin that I did pretty much straight on with just a little compound butter. The ribs were good sellers, the burger wasn’t too bad. I lived on those.

We had some of our celebrities who would come in had their favorites. Tom Barnard, he loved the burger. Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis loved our ribs. Kevin Garnett had just come to town to start playing and I had this pasta dish called Pink Adobe that was fettuccine in a cream sauce with chicken with a southwestern spice mixture so it came out pink, and Pink Adobe was a well-known restaurant in New Mexico.

We had oysters – and it was that era when everyone was smoking cigars so we had cigars at the bar people could buy. In fact, John Ashton from Beverly Hills Cop was in town filming that movie about the kid who takes over the Twins [Little Big League] and every night he’d come in and smoke a cigar and drink some whiskey and chat. So I got to know him pretty well.

HT: When you say ‘supper club,’ what do you mean?

NIDETZ: It’s like the Wisconsin aesthetic. Simple food, nothing too crazy. To me, it’s very comfortable food. It’s food you can relate to, food you want to come back for, something simple – we did fish fry Fridays. It’s not what supper clubs are now – there are some supper clubs out there with very modern, unique menus. And a lot of that food is not done well. And it doesn’t give the same effect to you when you walk in and it’s comforting food. Words like “umami,” “charred,” “foam” – they don’t belong in supper clubs.

HT: Tell me about Prairie Dogs – we reviewed it back in the day, you guys did a great Chicago dog there.

NIDETZ: A friend of mine in Chicago who had just bought with his partners a place called Devil Dogs – not Demon Dogs, there’s a Demon Dogs also – and they built a brand new store on the west side of Belmont.

They had the traditional Chicago hot dog but then my friend, who was a graduate of Johnson & Wales, he did all these gussied up hot dog things. That’s where the inspiration came from. I was at a low point with consulting, so I got Craig Johnson who had worked with me on several restaurants, I brought the concept to him, and he said sure. So we started doing pop ups, just to test things out.

It was all going well, people loved the food. But as we got into it, we realized the parking was the problem. There was no parking within short walking distance. When it’s 20 below and icy, no one was walking that distance. People were liking the food and the space, but we couldn’t make money on it. It’s like most restaurants, the margin at the bottom was so thin, if one thing goes wrong, it all goes away.

And people weren’t ready for an $11 hot dog. They probably are now. They looked at hot dogs in the grocery store and they could buy a whole pack for five bucks. I was ordering the hot dogs from Chicago, I was importing the buns – I had a bakery here making them but then they went out of business. And the sausages were being made for us by a butcher on the way to Brainerd.

HT: Prices really are climbing at restaurants these days…

NIDETZ: It will never come back down. If restaurants don’t raise their prices now they’re going to die. There’s no room now for not doing the things you should be doing for your staff – you should be paying a living wage and giving them insurance. The restaurant business really has to compete with the rest of the job market out there. The only way a restaurant can do that is raise their prices.

My whole thing is we need to dump the service charge and tipping so that everything the restaurant needs to pay its staff and operate comes from the price of food.

HT: You worked at the St. Paul Hotel in 1998 through 2000 – what was your brief there?

NIDETZ: The job was executive chef. A friend of mine was the F&B manager and he asked me to come in and fix what was going on with the St. Paul Grill. The last two chefs had turned it into a hotel dining room. It had no panache.

It was this supper club steakhouse, and they wanted me to bring that back, and that’s what I did. I got the costs in line and labor in line, but we went into this huge side hustle of catering… they were even looking into us creating food for one of the airlines, and that pulled a lot of the focus away.

HT: Can you put a finer point on what you mean by “panache”?

NIDETZ: Instead of meat and two on a plate with some sort of sauce, we went back to meat as a separate course, kind of what you see happening at Manny’s right now, which is a copy of the original Morton’s which I actually did some consulting for.

We had oysters, we had sauteed trout, very supper clubby sort of food that surrounded these steaks. We were cold smoking our own salmon and bringing that comfort feeling back into the food, and the luxury – so you didn’t see a menu that looked like 50 or 60 menus you’ve seen throughout your life. The word ‘grill’ was very potent for me.

HT: What do most (or all) successful restaurants have in common?

NIDETZ: There’s only one word to cover that, and it’s ‘hospitality.’ You have to really understand what hospitality is in order to survive. You have to be good at some of the business stuff as well, but if you don’t understand what real hospitality is, you’re going to piss people off one way or another.

That starts at the front door, into the bathrooms, through the kitchen and back out the front door again. The guests need to feel like they’re wanted, they’re special, and that you’re inviting them into your home so to speak, and treated very well while they’re there.

I would never have any of the front of house staff say ‘no.’ If a question comes up from the guest – and that’s another thing, never ‘customer,’ always ‘guest’ – they bring it to the manager or chef or whatever to see what can be done about it. And then if we have to say ‘no’ at that point it comes with an offer to do something else. It’s not a straight no.

HT: So if people want substitutions …

NIDETZ: ‘No substitutions’ – a lot of restaurants do that, but that never existed in anything I ever set up.

There was Andy at the Great Wall [Chinese Restaurant] in Edina, I went there for dinner shortly after they opened up, and he’d done a whole walleye with black beans and other stuff as a special one night… I went in there and asked him if they could do it, and he said ‘one moment,’ and then I see him running out the door to go to Byerly’s to get some walleye. That is ultimate hospitality.

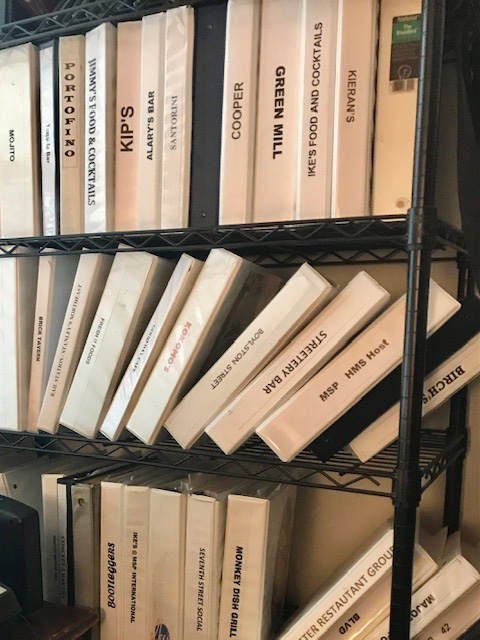

HT: Do you have to be born with that instinct for hospitality? Or can you teach it? Can you put it in a binder?

NIDETZ: Yes, yes, and yes. I’m looking at about 30-40 binders that I put together for various projects. And there’s a mention in all of them of hospitality, and that the word ‘guest’ is used instead of ‘customer,’ that you’re inviting them into your home, and we want the staff to treat the restaurant as a home environment… which is kind of difficult when you’re working for miniumum wage plus tips.

There’s a dichotomy there that can be solved with a living wage. You have to have a modicum of humanity. If you’re angry or judgemental, I’ll never be able to teach you, but if you’re open and willing to accept the concept of hospitality I can help you get better with it.

HT: Flip side – what are the signs a restaurant won’t make it?

NIDETZ: There’s the posting list that Minnesota Revenue puts out every week… if you’re on that, you’re probably going to go down the drain pretty soon.

But if you walk into a restaurant and you don’t get that hospitable feeling right away, they’re going to fail. Even if they’ve been there for 35 years, they’re at that point in that timeline that things are ending pretty soon.

White tablecloth is dying is because they can’t make money without having four or five interns not getting get paid, paying minimum wage to everyone else… and because of the waste factor in fine dining, having to throw out so much expensive food or repurpose it, which takes labor.

HT: This is reminding me of the upcoming closure of Noma, which was able to pull off their thing in part by relying on a big unpaid staff.

NIDETZ: I’m glad he [René Redzepi] did it [announced he’s closing]. The fine dining thing that chefs like René, and Grant [Achatz], and [Thomas] Keller are all trying to do really cannot be called ‘restaurants’ anymore. We need another name for that.

The only commonality is that they’re serving food. Everything else is in a different world. It’s a world of creativity, and it should be a world of super hospitality.