“Of course the Midwest is that part of the country that people long to leave,” writes Mark Kurlansky in the introduction to the “Middle West” section of The Food of a Younger Land. “The Midwest,” he adds, “is often thought of as the part of the country that isn’t a part of anywhere else.” And then, as a kicker: “the [Midwestern] cuisine has been ravaged by fast food.”

Kurlansky, a food historian and New Yorker, should be forgiven for his ignorance of contemporary Middle American gastronomy; with The Food of a Younger Land, he’s put together a damned fine book, coastal prejudices notwithstanding.

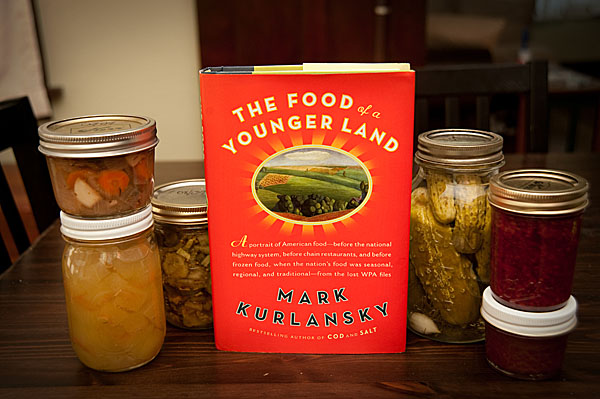

The book is an anthology of compiled and contextualized highlights from of a never-finished WPA Federal Writers’ Project called “America Eats.” The massive 1930s / 1940s project is now housed mostly in “five boxes filled with onionskin carbon copies.” The bones of this earlier, uncompleted effort to catalog American eating habits have been boiled down to make the rich stock that is The Food of a Younger Land.

By reviewing the work of hundreds of older writers (including the likes of Zora Neale Hurston, Nelson Algren, and Eudora Welty), Kurlansky has unearthed overflowing handfuls of gastronomic gems ranging from the semi-precious to the priceless. The book is richly packed with varied insights, including thoughts about what separates the clam and the quahog, or the history of cherry bounce (reputedly slaves filling mostly empty bottles of whiskey with fresh-picked cherries and letting the mixture steep until Christmas), or the “funeral cry” feast of the Choctaws of Oklahoma.

The Food of a Younger Land (Riverhead Books, $27.95, 397 pages) describes a set of regional gastronomic identities that have taken a post-World War II beating at the hands of mass-marketed, over-processed foods. Even when the writing is workmanlike — and it sometimes is — it contains fascinating and clearly rendered raw facts.

What emerges from The Food of a Younger Land is a grand portrait of American food heritage, quilted together from hundreds of small patches and squares of anecdote, reportage, recollection, and legend. The book turns the clock back to a period when meals were often eaten communally, such as the lutefisk suppers of Minnesota and Wisconsin, Vermont “sugaring-off” parties during the maple syruping season, and squirrel mulligan stew gatherings in Arkansas.

It’s also an implicit echo and amplification of slow food messiah Michael Pollan’s message from In Defense of Food: We Americans should consider going back to the diets of our grand-grandparents, the same diets that are depicted and celebrated by Kurlansky’s book. These are foods and food customs that predate the highway system, widespread chain restaurants, and frozen food — food that is, to quote the book’s cover, “seasonal, regional, and traditional.”

The truly lovely thing about The Food of a Younger Land is that it makes its points with concrete examples and massively wide-ranging reportage that feels fresh despite being frozen in amber. While there are points of contemporary commentary in the book — reflecting on how global warming has started to undermine maple sugaring in Vermont, for example — Kurlansky mostly steps back and lets the anthologized writers do the talking, contextualizing and guiding his readers only when necessary.

The work as a whole is entertaining, rich, and quietly but insistently thought-provoking. It’s broken up into small enough chunks that even our Twitter-addled brains can probably muddle through it, one story at a time. And it’s probably the only place to read about not only how to eat possum, but how to turn the practice into a longstanding “club,” complete with elected officers.

It may go without saying that not every food tradition is necessarily worth reviving.

A few Midwestern nuggets from the The Food of a Younger Land:

On Wisconsin Sour-Dough Pancakes: “The sour-dough pancake has always been a favorite food among Wisconsin lumberjacks, and few bull cooks worthy of the name fail to decorate their breakfast tables with huge platters stacked high with steaming, golden, sour-dough cakes.”

Kurlansky’s introduction for “Wisconsin and Minnesota Lutefisk,” on the Minnesota Writers’ Project article on lutefisk suppers: “The Minnesota story said that lutefisk provided ‘a sentimental link with the Scandinavian homeland,’ and also made the dubious claim that the slimy gelatinous fish ‘could safely be counted on to appeal to even the most finicky appetite.’ The Wisconsin report, with more candor, asserted: ‘Nobody likes lutefisk at first.'”

On the Minnesota Booya Picnic: “At the first hint of dawn, the preparations are under way. Oxtails, a meaty soup bone, veal and chicken are simmering in a huge vat, almost as high as the cook is tall, and as big around as three men.”

To some, the book may be worth buying for the booya recipe alone. Oh, what could be accomplished with a giant kettle and some generous underwriting from a far-sighted local butcher or grocery chain…

A traditional booya is an authentic MN experience that is not to be missed. I may have to pick this book up just get a look at this recipe. The only recipe I’ve ever seen is a hand painted one on an enormous sign almost the size of the kettle. It’s really a fun event and a great way to celebrate with friends.

“Food of a Younger Land” was good, though I thought he did skimp on the Midwest. Also, it’s a little too similar to “America Eats” by Pat Willard (http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/221961911) to escape notice (or vice versa – the pub dates are pretty close). I didn’t do an excerpt-by-excerpt comparison, but many of the exact same primary source quotes were given. Wonder if the authors ran into each other in the archives.