In May 2008, immigration officers raided Agriprocessors, a kosher meat processing plant in Postville, Iowa, detaining and deporting almost 400 illegal immigrants, about half the plant’s employees. In June of this year the former plant manager, Sholom Rubashkin, was acquitted of the child-labor charges brought against him, but sentenced to 27 years in prison for bank fraud.

The raid, which has become such a landmark that some refer to it simply as “Postville,” caused two things to happen: a temporary widespread shortage of kosher meat across the country and a nationwide conversation about the true meaning of kashrut, the Jewish dietary laws.

One of the leading voices in that conversation is Rabbi Morris Allen, leader of the Conservative congregation Beth Jacob in Mendota Heights. He wants to add a new hekhsher — a certification mark — right alongside the K, U, and OU symbols stamped on foods prepared under rabbinical certification and according to the laws of kashrut. This new mark is called the Magen Tzedek — the star of justice — because it will certify that the food is not only ritually correct but also ethically correct.

Rabbi Allen’s organization, the Hekhsher Tzedek Commission, has released more than 100 pages of ethical guidelines encompassing wages and benefits; health, safety, and training; corporate integrity; environmental impact; and product development, which includes animal welfare. Earlier this month, they announced that they will work with Social Accountability International to develop metrics for certification and they expect to see the first kosher food bearing the Magen Tzedek within a year.

Producers will pay an application fee to cover the costs of Hekhsher Tzedek’s and SAI’s work (both are nonprofits), just as they pay the traditional kosher certifiers now. Some have noted that this could raise the already elevated prices of kosher foods.

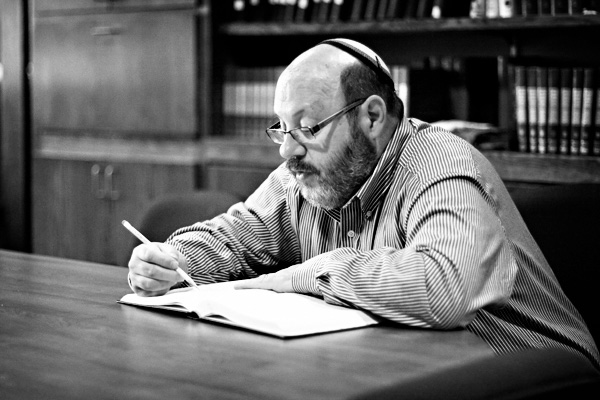

We talked with Rabbi Allen about Postville, kashrut, and the meaning of what we put in our mouths.

Postville brought meat-processing conditions into the national spotlight, but do the roots of the Magen Tzedek extend back before the raid?

Our work began long before the raid! Our work on Hekhsher Tzedek began in 2006 as a result of a story on Postville in The Forward [a Jewish Magazine] in May of 2006. I was part of a five-person crew that went down in August of 2006 and then went back to Agriprocessors in September 2006 with three recommendations: One, that the Iowa Department of Labor be invited in to do a scan of the plant which would have given Agriprocessors 18 months to respond to any of the findings. Two, that all trainings be done in the vernacular, which is, by and large, Spanish, and that all training materials be in Spanish. And three, that a series of meetings be organized between senior management of Agriprocessors, basically the Rubashkin family, and the workforce, with a letter signed by the Rubashkins stating that there be no intimidation or recriminations against people for whatever they said at those meetings.

They refused all three of those points and it was at that point in the fall of 2006 that we decided that trying to address [food production facilities] individually was not a wise thing to do. The Rubashkins may have been in the news, but we had no way of ensuring that other producers of kosher foods were not employing some of the same tactics. So we began in the fall of 2006 thinking through how to develop some sort of systemic approach to the production of kosher foods.

There have been a lot of people who post-raid jumped on the bandwagon, but the reality was that there was a bandwagon to jump onto because of the work that we had already done.

Why is this the right moment to be addressing ethics in kosher food production?

It’s an interesting question. Clearly in the larger environment there is a greater awareness of food and food issues. One could say this is part of something that is in the air, as it were, in the larger environment. But for us as Jews, food has always been central to our religious self-definition. The kosher laws in Hebrew scriptures are central to our understanding of self for many Jews. We held onto kashrut as an act of the sacred, as a means by which we brought the sacred into our daily lives.

So, eating matters.

What we discovered was that while people always thought that keeping kosher meant that there was something really sacred about the food, all of a sudden we began to discover that ritually the sacred quality had been protected, but there were ethical lapses. Several years ago the jingo for Hebrew National was “We respond to a higher authority.” That’s part of what we came to understand: We had to guarantee that we really were responding to a higher authority. That’s what kashrut really means.

Has there been resistance to the idea of an additional certification seal?

Sure. There’s always resistance by people who feel that somehow it’s a slight to their certification. There’s resistance because some people feel that this is not part of the traditional definition of kashrut. But I think that we have been successful in addressing those concerns. The major certifier of kashrut in this country, the OU, the Orthodox Union, has publicly said that they look forward to the day that a product certified by them will have our seal affixed to it as well.

We have worked to honor the people who do the work in the ritual certification and hopefully they will be able to honor our work in terms of the ethical aspects of certification.

What do you consider to be the real cornerstone principles of the Magen Tzedek certification requirements?

The way I would say this is that no longer will we be in the situation where we are more concerned with the smoothness of a cow’s lung than the dignity of a worker processing that meat. [The strictest kosher certifications require that the animal’s lungs be entirely free from lesions.]

To say it another way, the laws of kashrut are found in Leviticus chapter 11. In Deuteronomy chapter 24, it dictates how workers are to be treated. Leviticus chapter 11 is not written in large type and Deuteronomy chapter 24 is not written in small type, but ultimately they are written in the same size type and it is our responsibility to make sure that is the case.

How widespread do you someday see the Magen Tzedek becoming?

We think it will be pretty widespread! We think it will take time, obviously. But I think the fact that I and another rabbi involved in this project were two of the 50 most influential rabbis in America as identified by Newsweek in June is indicative of the fact that the larger American Jewish community has taken on an understanding of the work that we’re doing.

What are your plans for future growth of the seal? Will you take it outside the US, particularly to Israel?

There’s a little traction there, yes. We are very committed to making sure that we take this first step and succeed at this first step and once we are able to put this into the ballgame, as it were, it will take on a life of its own.

Learn more at the sites for Magen Tzedek and Jewish Community Action, as well as at Rabbi Allen’s blog.