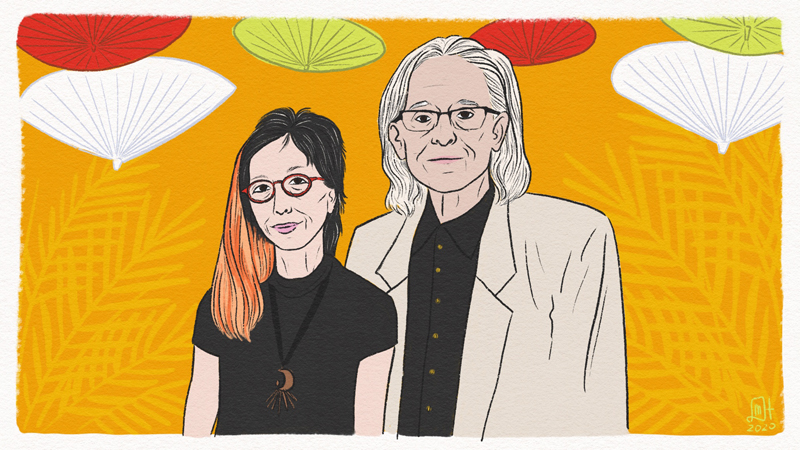

Illustrations by Lora Marie Hlavsa

Funding for the Heavy Table’s Lake Street Profiles series is provided by a grant from Peace Coffee and the Coffee Creates Community initiative. Lake Street Profiles is Heavy Table’s ongoing six-part series of conversations with culinary business owners on or near East Lake Street in Minneapolis.

In late May, in the midst of a raging pandemic already a grave threat to the business, Midori’s Floating World Cafe suffered grievous damage in the riots following the murder of George Floyd. Located just half a block from the Third Precinct, their windows were smashed in, and the restaurant was gutted and left in shambles. A former employee immediately set up a fundraiser on GoFundMe, which quickly brought in money that would be crucial to their survival. One look at the comments on the fundraiser’s page quickly reveals that Midori’s is a widely beloved institution—a fact that didn’t necessarily come as a surprise, but bolstered their desire to stick it out at any cost.

“We knew that a lot of people really loved the restaurant,” co-owner John Flomer says. “Our customers, some of them have been coming in since the day we opened. “They’ve brought their families there, they’ve celebrated birthdays, they’ve celebrated marriages, graduations – they’ve celebrated there and it’s a part of their history. In a way, that was important to us. It’s probably as important as our desire to just stay up there and make a living.”

Midori and John Flomer never set out to open a Japanese restaurant – before they opened the restaurant in 2003, they were both artists weighing the idea of opening a small tea shop and deli specializing in food from around the Pacific Rim. Luckily, a building developer they were working with was hungry for a new sushi bar, and talked them into expanding their concept.

“We got so into that situation without having any idea at all how to run a restaurant,” John says. “We didn’t even know how to run a tea bar.”

“We weren’t even chefs,” adds Midori.

Having met as students in visual arts at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design – Midori hailing from Nagasaki, Japan, and John from the East Coast – the pair found that their artistic prowess came in handy in running the restaurant. Midori applied her artistic vision to making the sushi, and John focused on designing the eye-catching space, menus, and marketing. On the other hand, they were effectively flying blind when it came to running the business. “We’re not business people,” says John. “We don’t even understand that world, and I’m not sure we even still understand it. There’s a science to that. What we know is learned by being in the trenches.”

Having met as students in visual arts at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design – Midori hailing from Nagasaki, Japan, and John from the East Coast – the pair found that their artistic prowess came in handy in running the restaurant. Midori applied her artistic vision to making the sushi, and John focused on designing the eye-catching space, menus, and marketing. On the other hand, they were effectively flying blind when it came to running the business. “We’re not business people,” says John. “We don’t even understand that world, and I’m not sure we even still understand it. There’s a science to that. What we know is learned by being in the trenches.”

From then to where they’re at now, they credit luck – both the good and the bad – to their restaurant’s longevity. Thriving in their first space, in the same building that housed Gandhi Mahal before it was destroyed in the riots, the pair decided to expand with a larger restaurant in 2009, moving to their most current Lake Street location. But just as the ink was drying on their new lease, that plan came to a crashing halt when the economy crashed, leaving them with greatly increased rent and tens of thousands of dollars invested in the buildout. Over the next few challenging years, John admits that he considered calling it quits.

“I wanted to give up, but Midori wanted to keep it going,” John says. Midori says it was the love from their customers and staff that inspired her to keep pushing on—and after so many years in the kitchen, she wasn’t interested in doing anything else.

Along with money raised by the community following the riots, neighborhood business associations like the Lake Street Council and Seward Redesign jumped at the chance to offer a hand wherever they could. The trouble remains that, financially, Midori and John are stuck in a complete standstill with their ruined location.

“Because of the building being in limbo, we can’t do anything. So the help that we’ve been offered, it just sits there and eventually it will dry up,” John says. “So actually we probably would’ve been better [off] if the building had come down with the other buildings, and then things could’ve moved forward.”

As for any assistance from the government, John says they’ve received no financial assistance whatsoever despite applying for several small business loans. The Flomers aren’t holding their breath for any small business aid on this latest stimulus package. “To tell you the truth, I’m not counting on any of that,” he says. “That money I don’t think was ever for us.” The credit for their survival lands squarely on the shoulders of their supporters and neighborhood associations, and in the hopes that they can break their lease and find a new location, they’re set on staying in the Seward/Longfellow area. “We’re not really going to move on that unless we become desperate,” John says. “We want to stay here because our customers are here.”

The duo are eyeing smaller spaces to downsize the operation and focus more on takeout and reservations. While it might paint a dark picture, John is begrudgingly realistic about the future. “We think this is going to be going for a long time, and it’s not going to be the last pandemic,” he says. “Going forward, everything is an unknown right now. To go back into business with huge rent and employees and a huge overhead is kind of scary when we don’t know what’s happening.”

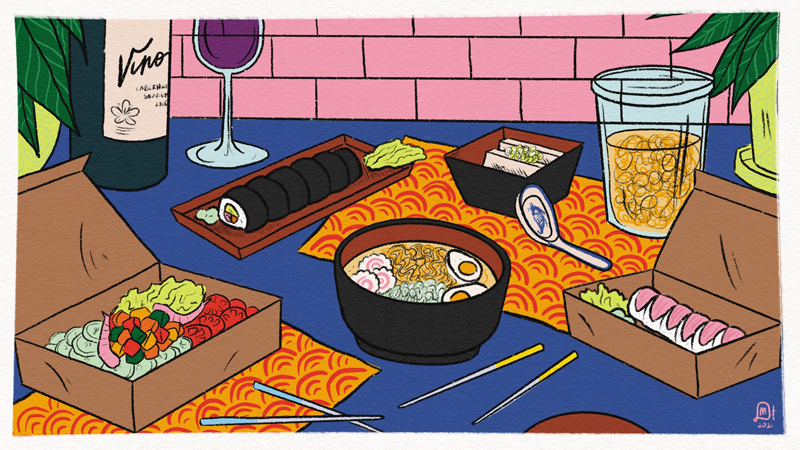

The Lake Street Council along with the Neighborhood Development Center have assigned pro bono lawyers to deal with their landlord—until a resolution is reached, the pair have set up shop temporarily in the Seward Cafe, offering takeout on the weekends (which started January 2.) They still offer sushi and rice bowls but, with a limited kitchen lacking a deep fryer, they’ve had to cut back on their tempura. Still, they say they’re excited to help Seward Cafe keep its doors open, while admitting some apprehension about being back in the kitchen.

The Lake Street Council along with the Neighborhood Development Center have assigned pro bono lawyers to deal with their landlord—until a resolution is reached, the pair have set up shop temporarily in the Seward Cafe, offering takeout on the weekends (which started January 2.) They still offer sushi and rice bowls but, with a limited kitchen lacking a deep fryer, they’ve had to cut back on their tempura. Still, they say they’re excited to help Seward Cafe keep its doors open, while admitting some apprehension about being back in the kitchen.

“I’m scared about that,” Midori plainly states.

“We haven’t cooked since the end of May,” adds John.

Though they’ve weathered more than their fair share of hardships in their efforts to keep the business running for the better part of the last 18 years—and this year there’ve been more than ever—the harsh realities of the running a business are still outweighed by the satisfaction they feel from serving their loyal customers.

“Our accountant said ‘You know, you could make more money working for somebody else.’ And we probably could make more money working for somebody else,” John says. “The best part of not being business people is: we’re not really in it for the money. That sounds ridiculous, but even as an artist from my perspective, I’ve never done art or music for the money. I’ve done it for the love of it. And I think it’s the same thing with the restaurant—you do something for the love of it.”