Editor’s Note, 7-16-15: Since the publication of this story, it has come to light that the people behind Templeton Rye have not been entirely honest in their promotion of the way their whiskey is produced and marketed – culminating in a recently settled lawsuit over its dishonestly presented provenance. The whiskey is not yet made in Templeton, Iowa; rather, it’s produced by a contract distillery in Indiana then blended and bottled in Iowa. Despite the potentially shady side of Templeton Rye, we still believe it to be a fine whiskey regardless of where it’s produced, and leave it to the reader to determine whether it’s worth purchasing given its unraveling backstory.

You know Al Capone only drank the good stuff.

His whiskey of choice was Templeton Rye, a flavorful, smooth whiskey made by the enterprising farmers of Templeton, Iowa, that has finally become legitimate after nearly a century of production on the sly.

The story of Templeton, pop. 350, and its whiskey-making farmers began with homemade stills during the post-World War I Depression and has evolved into a thriving business owned by Scott Bush, 34, a Templeton-area native who was determined to bring the bootleg booze — and its history — to the masses.

“It saved the farm back during Prohibition,” Bush says.

Times weren’t great when Prohibition began. The Roaring Twenties have an image of speakeasy-fueled, “Gatsby” mayhem, but in the Midwest it was struggle as usual. Farmers were doing all they could to feed their families.

“Rye was sort of the last grain on the farm,” Bush says. “Back then, there was a lot more sustainable farming going on where they wouldn’t let anything go to waste. If there wasn’t a market for a crop, they would find something to do with it.”

Some Templeton farmers started experimenting with whiskey. They were pretty good at it, and their reputation spread.

That’s when Capone came in. Good liquor during prohibition was hard to find — speakeasies were deathtraps where homemade, bathtub booze could render drinkers paralyzed or even dead. So for those who could afford its $5.50 per gallon cost ($75 in today’s dollars), Templeton Rye was a good drink made from clean ingredients.

“If you had the means, you would drink Templeton Rye and you could be assured that you were getting the highest quality,” Bush says.

One Templeton-area native, Ron Hodne, tells of driving a truck through Chicago and running into an old-timer who, learning Hodne was from Iowa, told him he used to run Templeton Rye for Capone.

“These farmers from Western Iowa refused to cut corners and continued to make their product with a lot of pride and a lot of care,” Bush says. “When the Capone gang got ahold of it, it really because famous and was known as the best whiskey in the house across the country.”

Bush adds, “They say that there was 10 truckloads a week heading from Templeton to Chicago.”

Prohibition ended in 1933 but not for the Templeton farmers, who continued production in small, illegal batches for decades until Bush became determined to resurrect the whiskey legally. Bush’s great-grandfather, Frank, made Templeton Rye in his farm still, and his grandfather told him stories about growing up with the Rye. In 2005, after Bush struggled to finally procure the recipe from reluctant locals, the whiskey was rolled out to the public.

But this story seems fantastic. Clean-cut Midwesterners like Iowans just don’t break the law running booze.

When you’re dirt poor, though, feeding your kids comes first.

“The one thing that folks around here value more than law is their family,” says Bush. “My grandpa would say, ‘I don’t think younger generations have any understanding of how tough it was back then.’ It got pretty desperate for a way to feed people.

“Also, from day one, people looked at Prohibition as kind of a joke. It was one of those laws that people thought, common-sense-wise, didn’t make a lot of sense.”

But it was still illegal, and these farmers weren’t hard-boiled gangsters, either.

“It was shameful to be caught or busted,” says Bush. “There are still folks out there who won’t talk to us about those stories because they’re still ashamed that their great-grandfather got nabbed by the police.”

At its height, pretty much everybody in Templeton was involved in some way with the trade. But since the recipe wasn’t exactly carved in stone on the county courthouse, Bush asked for help from a friend, Keith Kerkhoff, whose grandfather, Alphonse, also had a still. Piecing together family lore and interviews with old-timers, they unearthed Alphonse Kerkhoff’s recipe for Templeton Rye.

“There’s not a lot of documentation because it was always illegal,” Bush says. “So there’s a lot of really true, good, unique history of Iowa, the Midwest, and prohibition that’s going to die if we don’t go out and tell these stories.”

Like, what happened when the law came calling?

“Whenever the feds came to town, they would have to grab the local sheriff,” says Bush. “They [the bootleggers] would make the woman at the phone company make line calls to let them know they were coming.”

And the sheriff wasn’t selling anybody out. Whenever the feds were near he made sure to wear a hat — a signal for the farmers.

“The sheriff never wore a hat unless the feds were in town,” Bush says. “The Kerkhoff family… Alphonse got busted twice.”

Nobody’s getting busted today. A burgeoning craft whiskey movement, much like the craft beer explosion of the past 20 years, is hoping to carve a niche into the mass-produced liquor market and prove that good whiskey doesn’t have to be made in Kentucky, Ireland, or Scotland. Death’s Door produces whiskey in Door County, Wisconsin; McCarthy’s is making single malt in Oregon; Tuthilltown Spirits of New York churns out rye, single malt whiskeys, and bourbon.

“It kind of falls in the with the whole organic / local thing,” Bush says. “It’s been really neat — it’s such a new market.

“It’s small, a, and b, it’s cool because it’s a very open endeavor between craft distillers. If you added up all our revenue we’d be less than one percent of Jack Daniels. We’re really not competing with one another, we’re competing with the big guys.”

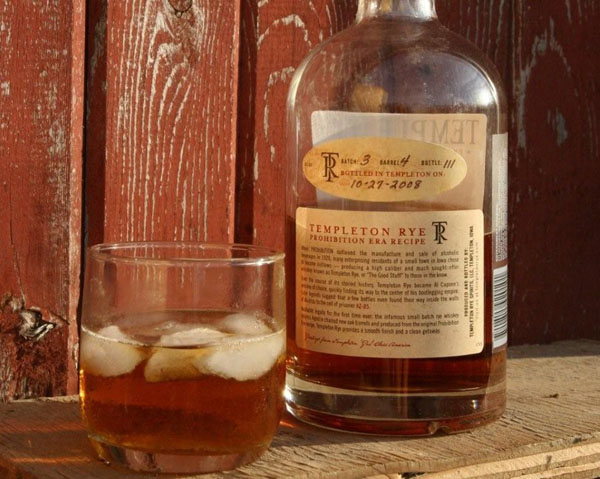

Templeton Rye, a single-malt, single-barrel rye, is made from a mash of more than 90 percent rye. (To be certified rye, a whiskey’s mash must contain at least 51 percent rye). It is aged more than four years in charred new white-oak barrels. The fledgling company has had trouble keeping up with pent-up demand due to the four-year aging process — a recent Des Moines Register story detailed liquor distributors’ frustration with the low supply.

In June 2008, Templeton Rye was named Best Overall Whiskey out of more than 4,000 entries at the Los Angeles Wine and Spirits Competition and won a gold medal in March at the San Francisco World Spirits Tasting. It was also named the best whiskey under 10 years old by Whiskey Bible.

“Rye has this huge character,” Bush says. “The knock on rye is that sometimes they’re a little bit harsh. It’s all about balance. We feel that we have a ton of character on the front, and Templeton has always been known for its smooth finish, and I think that’s where a lot of our success has come from.”

Drink it with just a couple of ice cubes. Or it makes a terrific Manhattan, with just bitters, sweet vermouth, and a cherry.

“You start adding sugar, fruit juice to spirit, it can get overpowered quite easily,” Bush says. “That’s one of the big reasons rye whiskey is getting so popular again.”

But the biggest question: When will Templeton Rye be available in Minnesota? “Minnesota will be our next market,” says Bush, who added that he’s heard from a lot of Minnesotans with their own Templeton Rye stories.

But expansion will take time. As a nascent distillery, it’s difficult to gauge public reaction to your product. If you make too much and nobody buys it, there’s a glut. If you don’t anticipate extraordinary demand — like that for Templeton Rye — it takes awhile to react and beef up supplies.

“There’s a reason you don’t see small whiskey companies — we’re putting whiskey away that we don’t drink until 2014,” Bush says. “We’re in this situation — we’re still a small company. We only have available what we have. We’ve been very patiently growing our inventory. Late 2010 is when some of the expanded inventory will become available.”

Can’t wait? It’s available at www.binnys.com for $34.99 and at internetwines.com for $48.53.

As one Templeton old-timer says, “There really wasn’t much said about it. It was just a known fact that Templeton Rye was available, but you didn’t know where it come from and there was certain people who could get it for you.”

Or, as Bush put it, “Anybody from west of Des Moines is within two degrees of separation from somebody who was involved with Templeton Rye.”

For more stories from Templeton old-timers, go to www.youtube.com/templetonryewhiskey.

Very well researched piece. I have one full and one almost empty bottle of The Good Stuff in my wet bar. It’s become my sipping whiskey of choice. Even trying to wean my father-in-law off a 30-year-long Jack Daniels’ habit with it, to moderate success.

Templeton really was at the outer reaches of the Rye Diaspora. Here’s a shoddily written link-blog I did on Rye a few months back on how it got there. http://shefzilla.com/?p=1798

Also, there’s a

Just saw a piece on Capone last night on History and it wasn’t nearly as intriguing as this.

Great, tasty Americana writing – interested in how the recipe was “preserved” … did the old-timers “farmers” keep it on paper, or recite it all from memory?

Keep ’em coming.

Great article and wonderful pictures.

Too bad it’s so hard to get in Des Moines. We’ve run out.

Great article, well-written! This margarita drinker is thinking she’ll have to try it. Thanks for the good article and pictures.

Just got a bottle last night. It lives up to it’s name.

Too bad most of the story is a marketer’s fairy tale.

If you believed any of the above story, and you bought any Templeton Rye, you may be entitled to a rebate.

Templeton Rye will have to add “distilled in Indiana” to its label, where it comes from the same industrial distiller that produces a lot of different brands. The flavor is a chemical mix from a flavoring company.

Also Templeton Rye must remove the claims about “small batch” and “Prohibition era recipe,” both quite prominent in the pictures of the bottle in this article.

The rebates, along with the labeling changes, are in a proposed class action settlement filed with the court in Chicago.

Here is the story in the Chicago Tribune:

http://www.chicagotribune.com/dining/ct-templeton-rye-settlement-20150714-story.html