This story is sponsored by the University of Minnesota Press – check out their end of the summer 30% book sale.

The earliest recorded example of butter sculpture was Dreaming Iolanthe by Caroline S. Brooks, which displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Since then, of course, butter sculpture has become a very popular activity to check out at the Minnesota State Fair, among other state fairs. Here’s some more background on this much-buzzed-about art form and its earliest pioneers.

Excerpted from Corn Palaces and Butter Queens: A History of Crop Art and Dairy Sculpture by Pamela H. Simpson (2012, University of Minnesota Press).

John K. Daniels, Professional Butter Sculptor

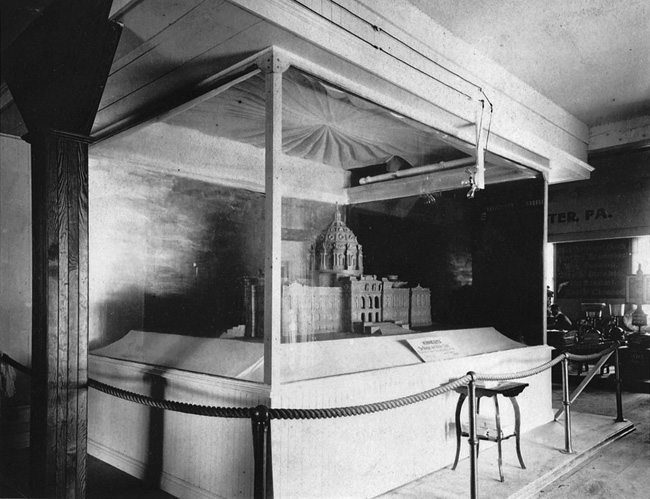

The work of John K. Daniels (1875–1918) provides a good example of the professionalization of butter sculpture. Daniels emigrated from Norway to Minnesota with his family when he was nine. He grew up in Saint Paul and trained there in several art schools and with two different sculptors before setting up his own studio. Like most sculptors, he modeled in clay and put his finished pieces into stone and bronze. In 1900, to earn some extra money, he accepted a commission to make a butter cow for the Minnesota State Fair. His fame as a butter sculptor, however, was established the following year, when he created a spectacular model of the Minnesota state capitol for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. The State House, designed by renowned architect Cass Gilbert, was still unfinished in 1901, but it was the pride of the state. The board of managers for the Minnesota Exhibit wanted to show a plaster model, but there was not enough time or money to make one. Daniels offered to do it in butter for two thousand dollars. Working with an assistant, he took six weeks to make the 11′ × 5′4″ model. The two men spent fifteen-hour days in a glass case cooled to thirty-five degrees Fahrenheit, and were so “chilled to the bone” that they had to take frequent breaks to warm their hands.

Initially the temperature was maintained with ice, but by the time the piece was finished, the fair’s electrical refrigeration system was in place; it kept the model well preserved for the whole length of the exposition—some eight months, rather than the normal week or two of a state fair. The “hundreds of thousands” of visitors who came to marvel at the exhibit also carried away a souvenir pamphlet prepared by the Chicago, Saint Paul, Minneapolis, and Omaha Railroad. The brochure pictured the butter model and described its making, and also included statistics on the dairy counties in the state. As the official report noted, visitors carried this publication home as “indisputable proof” that Minnesota was the nation’s “bread and butter state.”

Daniels followed the Pan-American triumph with an even more impressive exhibit at the Saint Louis Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904. Saint Louis had the biggest dairy display of any international exposition to that date. A whole building was devoted to the industry. On one side of a long aisle was the story of butter production, from cow’s milk to finished product, with every step illustrated by live demonstrations. On the other side, in a refrigerated, glassed-in section, was the butter sculpture. Almost every state with a dairy interest was represented. For Minnesota, Daniels modeled two life-size pieces, one a figural group of Father Hennepin and his two guides in a canoe discovering the Saint Anthony Falls, and the other, a woman on a pedestal offering a slice of buttered bread to her young son. As one Minnesota newspaper noted, “There is not an exhibit that attracts more attention and does more good advertising than these two butter models” that represent the “principal industry” of the state.

Wisconsin showed a dairymaid and her cow. Washington State exhibited a dairymaid milking a cow and squirting a stream to a hungry kitten. Missouri offered an elaborate composition of the goddess Ceres holding a scythe, accompanied by two cows standing before a bas-relief background of the state seal and images illustrating the progress of the state’s dairy industry. Nebraska’s sculpture was a cornucopia; Iowa had flowers, a portrait bust of dairy leader John Stewart, and a small model of its new state dairy college; Kansas had a model of its own new agricultural college, along with a life-size image of a woman turning away from an overturned butter churn and toward a modern cream separator. There were at least two Theodore Roosevelt portraits, one a portrait bust from New York, the other an equestrian statue from North Dakota. All of this was in butter.

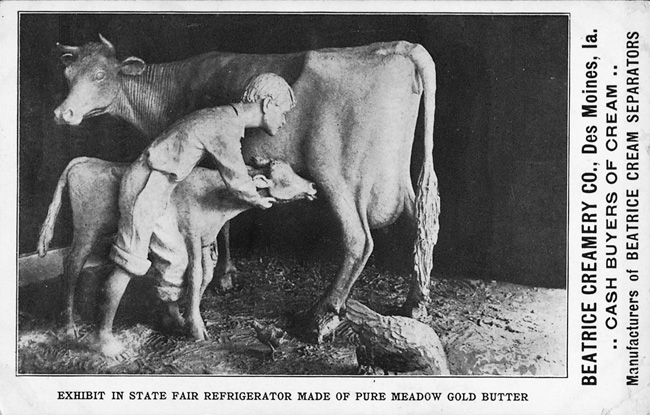

Although the displays at the great international fairs were the most impressive, Daniels and others continued to make sculpture for state fairs and the various national dairy meetings as well. Sponsored by one of the creamery companies, he provided many butter cows, including a popular one of a little boy helping a calf learn to nurse from its mother. He also regularly supplied a butter portrait of the sitting governor for the Minnesota fair, and in 1906, he modeled portraits of the Wisconsin governor, the secretary of the United States Department of Agriculture, and the mayor of Chicago for the National Butter Makers Convention and Dairy Show at the Chicago Coliseum. In 1910, in honor of Theodore Roosevelt’s return from a yearlong safari in Africa, Daniels made a butter statue of the former president, gun in hand, standing over a dead lion. That was the same year Roosevelt visited the Minnesota fair as part of his reentry into politics. Daniels turned to more traditional materials in the 1930s and earned his fame in marble and bronze.

The practical side of making butter sculpture

“How long will it last?” [Question posed by King George V of England at the 1924 British Empire Exhibition.]

The king’s question was a good one. With proper refrigeration, butter sculpture lasted the length of the average fair, usually six to eight months; then the butter would be stored and later reused for more butter sculpture, or reprocessed for animal feed or nonedible uses such as soap.

The method for sculpting in butter was similar to that for clay modeling. For three-dimensional work, a metal or wooden armature supported the weight; wire mesh, or some other material was wrapped around that, and the butter was applied over it. One sculptor reported seeing smaller pieces in England made with a thin layer of butter over a wooden form, and we can speculate that any display that included a table, stool, or bucket probably had a real table, stool, or bucket simply covered in butter, but the main sculptural figures—cows, people, and animals—were always done with an armature. The key was to have as much butter as possible in the piece, something the advertising always boasted about with claims of how many hundreds of pounds of butter went into the exhibit. Some smaller works, such as portrait busts, were carved out of a solid block instead of being modeled; but for the larger pieces an armature was necessary.

The youthful sculptor Mahonri Young learned this fact the hard way. In 1906, newly returned from his studies in Paris and greatly in need of funds, he gladly accepted a commission to model a dairymaid for the Utah State Fair. Presented with a large block of butter, he directly carved a 40-inch-tall dairymaid and assumed the refrigerated case would keep the butter frozen. After days of labor, he finished the piece, carefully closed the case door, and went off to enjoy the rest of the fair. Several hours later, a man ran up to him, yelling, “The woman is melting!” Young hurried back to find that someone had opened the case door and the warming butter had caused the woman’s head to sink into her chest. He repaired it using enough butter, he said, to make her look like “she had a goiter.” If he had employed an armature, this would not have been necessary. The warming butter might have softened and lost some detail, but it would not have begun its collapse. Even frozen butter does not have the tensile or compressive strength of stone. It is much easier to treat butter as a substitute for clay.

Young’s experience with the melting maiden reinforces the point that butter needed to be sculpted in the cold. He may have had a case cooled to freezing when he started, but most butter sculptors worked in temperatures similar to those of a home refrigerator, from the mid-thirties to the low forties Fahrenheit. The reporter for one London newspaper joked about finding a group of sculptors laboring away in a refrigerated case in April during a late-spring snowstorm; the gas motor creating the cold inside the case seemed a little redundant, given what was happening outside.

The rise of these professionals did not eliminate the presence of amateur artists. It may even have legitimized the genre for them. Women artists who came to butter sculpture through a connection with the dairy industry continued to make contributions. In the early 1900s, Alice Cooksley, wife of an Illinois creamery manager, started turning butter into delicately colored flower arrangements in the cold workrooms of her husband’s company during the evening hours. Born and raised in England, she had some art training but was not a practicing artist. One day while visiting her husband’s creamery, she remembered butter displays in London in which small wooden models of cows and dogs had been covered with a coating of butter. She thought she might try her hand at it, but she wanted to model flowers out of pure butter without the wooden forms. It took her many evenings of experimentation in the refrigerators to perfect her art. She even took courses at both the Illinois and Iowa state agricultural colleges to learn more about butter and its properties, and she designed her own tools and refrigerated workspace. “There were many lonely nights in that icy refrigerator,” she said, resigned to the fact that “being a pioneer in any field has its disadvantages.” But she also joked that if others could “starve for their art, I suppose I can freeze for mine.” Her work at the Panama–Pacific Exposition in San Francisco in 1915 earned her widespread accolades. She and her husband moved to San Francisco, where she continued to exhibit at state and county fairs and gave demonstrations for dairy association meetings. By 1927, she was reported to have exhibited in twelve states and several Canadian provinces.