“Even an experienced fisherman, seeing swallows swarming above the stream, and fish rising avidly, can fail to perceive what all the fuss is about until he crouches to examine the river’s surface. There he will see a flotilla of lilliputian sailboats, the mayflies with their wings erect, actually standing on the surface film, their wee feet dimpling the surface.”

Since 2008, Brett Laidlaw’s blog Trout Caviar has allowed us to tag along on his bucolic ambles, foraging through woods, streams, cheese shops, and farmers markets and, almost always, emerging with the ingredients for a fine meal. (Indeed, the sentences quoted above lead to a brown trout, the anchor in a cold supper of salad, chevre, and artisanal bread.)

Laidlaw’s poetic descriptions of life in his primitive, Wisconsin cabin, Bide-A-Wee, and the food-laden fields and streams that surround it, cast him as a mash-up of Thoreau and a kind of forager’s Julia Child. He is equal parts nature and food writer. And, though he often writes of farm-grown and locally produced foods, his blog makes wild foods less intimidating by identifying the rare or long-forgotten sorrel, honey mushrooms, and chokecherries and using them in tasty yet not too precious recipes.

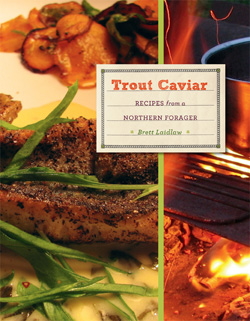

Fans of the blog will be pleased to discover that Laidlaw’s new book, Trout Caviar: Recipes from a Northern Forager (261 pages, $27.95), is equally delightful to read and packed with anecdotes and recipes, many of which are brand new.

Here he talks about the new book, sustainable foraging, the joys of shopping — and how, contrary to popular belief, most of nature is edible. Plus, he gives us the recipe for his reconstructed coleslaw.

THE HEAVY TABLE: You take a pretty broad view of foraging – can you explain your philosophy?

BRETT LAIDLAW: That’s sort of the theme of the whole book, I think there’s a lot of interest in wild foraged foods lately, and I’ve done that for a long time, but I don’t eat that way exclusively and I doubt that many people do. So, I wanted to make the book more accessible, but also to stress the importance of getting really good ingredients wherever they come from.

HT: In the blog, I get the impression that you kind of scurry about, over the course of your day, popping over here for this or there for that – sort of gathering ingredients.

BL: In my shopping and foraging, I’ve gotten to the point where I rarely set foot in a big grocery store – you know, I’ll buy paper towels and toilet paper, and that’s about it. So it’s the co-op, farmers markets, the garden, and smaller shops, like Clancey’s or a cheese shop. I say in the introduction that 90 percent of good cooking is good shopping, taking shopping in a very broad sense of getting the best local, seasonal ingredients and doing the best that you can by them. I don’t mind spending a lot of time gathering the ingredients of meal because it’s a pleasure to pop into Clancey’s and see what crazy cuts of meat they’ve got in — and I get really inspired to cook through that, too.

HT: It’s a different model of shopping – you know, get what you feel like eating and what looks good, rather than cramming all of your shopping into one giant store, one day a week.

BL: It’s a bit like the French market model. Unfortunately things are maybe more spread out around here, so there’s often driving involved. It would be nice if, you know, we lived on the left bank and you could just go out with your string bag and hit the charcuterie, the cheese shop, and the market and bring it all home in the course of a nice walk. You can kind of do that at the farmers markets here. I’ve really been enjoying going down to the Minneapolis Lyndale market on weekdays this summer. It’s not a full scale market; there’s not a lot of meat, but you can get all the vegetables you want and it’s a much more mellow scene than on the weekends.

HT: In the book, you write vividly of fishing and picking wild blueberries as a kid, but how did you become comfortable with foraging for the more wild and oft hard to recognize stuff – mushrooms, in particular?

BL:

Well, I had an interest in wild foods even as a little kid, even though I didn’t act on it. I probably would have killed myself if I had. I think it really began when I started trout fishing in the ’90s. I fished with people who had a bit of knowledge about wild foods. There’s some pretty easy ones out there: An oyster mushroom in the wild looks exactly like an oyster mushroom at United Noodles. And I know I’ve written about walking along a trout stream and just smelling this chive-y, onion-y aroma come up and envelop me and wondering what it was — it turned out to be ramps, which can be really abundant. I never committed myself to a real effort to study, but as I learned I could get ramps to sauté up with my trout, and maybe some nice steamed nettles and watercress salad to go alongside it, I became intrigued enough to get some good books. I really try to learn one or two new wild foods a year and broaden my repertoire that way, very gradually.

HT: In that post about the ramps, you talk about harvesting them in a very specific way so as not to take out the whole patch. In terms of traditional foraging, do you think sustainability is an issue — say in the case of popular stuff like ramps, morels, etc.?

BL: I don’t see the foraging community here becoming so big that any particular species of wild plant or mushroom is going to be endangered. But, in other parts of country, there are people foraging closer to large metropolitan areas, where there are a lot of markets and restaurants interested in wild foods. It’s anecdotal, but I’ve read stories about seemingly inexhaustible patches of ramps in a forest just disappearing. Ramps grow in a cluster that’s joined together under the soil. It can take up to ten years for a clump of ramps to grow to that size, so the responsible way to do it is to dig around the edges and just take a couple ramps from each clump. I think it’s an important part of the whole foraging experience to be aware of the natural world that you are in and that you’re exploiting for your dinner. Most good foraging books address that topic. I am particularly fond of Sam Thayer’s books, The Forager’s Harvest and Nature’s Garden, as well as my friend Teresa Marrone’s book Abundantly Wild. They’re great because they’re both local and foraging here.

HT: Do you have maps of the spots where you’ve found goodies? For years, I’ve coveted a friend’s map of great asparagus foraging spots along the highway.

BL: I should make a map — and it’s funny that you mention asparagus because those bright yellow-green ferns are all over the ditches of Wisconsin and Minnesota right now, so this is the time to go out and find it and remember it for next spring. But you know, for most other things, I go back to the same woods a lot, so I tend to know where the chanterelles are going to be. I also just like meandering through the woods, from one oak tree to the next, hoping there will be a hen of the woods. Sometimes I get turned around a little bit, but that’s part of the fun. I hope it comes through that I forage more for the pleasure of being out in the woods, and the edibles that come home from the foray are just kind of the frosting on the cake, to use a bad cliche.

HT: In your walks, you seem to see food all over the place – that must be nice.

BL: Another thing I picked up from Sam Thayer is the recognition that — while a lot of people think that the majority of wild plants will kill you and there are only a few select edibles out there and you have to be very skilled to find them — it’s actually almost the opposite. You can go out and point at things in a natural landscape and see that most of them are either edible or at least not dangerous. Not all may be really delicious or desirable, but it’s a much more benign environment than I think most people realize, the woods, in terms of food.

HT: What’s a really thrilling find? Or, conversely, is there anything you’ve tried to love, that you know is edible, but you just can’t get there?

BL: I’m always just as excited as can be to see first chanterelles of the summer, even though they are really easy to find because they are bright orange-yellow and stand out so much in the landscape. I was really resistant to nettles for a long time, I think because of those experiences of being tortured by nettles getting to and from the the trout stream. They are so abundant in a lot of places, and you kind of take them for granted, but they’re great, especially the first little sprouts, which you can just steam up and sort of get the first taste of local greenery in springtime.

HT: Can you explain your take on local — the Trout Caviar manifesto: “Our stuff is as good as anybody’s stuff, and part of the reason it’s good is that it’s ours.”

BL:It’s difficult to explain, I feel it kind of viscerally, that connection to these local ingredients. There has been this huge boom in interest in local and seasonal foods, but I think it’s when you get to the wild foods, the stuff that’s really of this place, that it reaches its highest expression. But even though we have a lot of chefs emphasizing that they got this chicken from this farm and use this lettuce from this grower, they might still end up sprinkling Parmigiana Reggiano on it or frying it in olive oil. And maybe that’s the next step: not necessarily rejecting food from other places, but appreciating what we do have here and finding different uses for it in our cooking, which is not to say that I don’t use olive oil — but I don’t buy Parmigiana Reggiano anymore. If I want something like that, I’ll look for a 10-year-old cheddar or an aged Gouda from Minnesota or Wisconsin and see how that works. I don’t want to be doctrinaire about it either – I think people should do what they want, and if they really love imported cheese or whatever else, then, you know, do it. But I think there’s still a world of local foods that are underappreciated and deserve to get more attention.

HT: You use the word “authentic” a lot, but you do love to do things like make pesto with “other” herbs, cheeses, and nuts. What does it mean to be authentic?

BL: I think it has to do with looking at ingredients without preconceived notions about whether they’re high, low, fancy, or plain and trying to understand the inherent qualities of the ingredient. The popcorn salad recipe comes to mind for some reason because it’s just a screwball recipe that this woman Cindy Plash sent to me, when I did a blog post about Clem’s Homegrown Popcorn — Clem is her father-in-law. And it was just so bizarre that I had to try it. I changed the recipe considerably; I added more popcorn and combined it with really good sharp Wisconsin cheddar, my beloved Hellmann’s mayonnaise, some celery and stuff and it was this… nobody would call it haute cuisine or anything… but just really down-home cooking. Everyone loves popcorn, but we don’t even think of it as an ingredient. So, it’s not about authentic cuisine, not about cooking a pasta dish they way the Italians would do it, but taking ingredients on their own terms and letting them speak to you in the kitchen.

HT: In the book you talk about how you came to food, but how did you learn to cook it?

BL: I think with everything else I’ve done, just really gradually. I became a vegetarian in high school — I don’t remember why, now — so I kind of had to learn to fend for myself.

HT: What happened? Your folks said, “Sure, you can stop eating meat, but we’re not going to change our diet; you’re on your own, kid?”

BL: Well, kind of. My mom was somewhat accommodating, but she didn’t really have a repertoire of vegetarian dishes. So I remember picking up the Vegetarian Epicure and The Moosewood Cookbook and kind of flipping through them and seeing what I could make.

I think my cooking really took off in the late ’80s. I had this opportunity to go and teach English at Sichuan University, in Chengdu. I had a two-burner gas cooktop in my apartment and a tiny refrigerator. That was kind of a luxury; most Chinese didn’t have refrigerators at that point. I shopped in market almost every day and cooked for myself without a cookbook. My students would come over to my apartment and just tear the place apart, making dumpling or Sichuan hot pot. I learned everything I could from those guys; they all seemed to be instinctive cooks. And that was a shop-in-the-market-every-day kind of place. There were no supermarkets, just tiny shops and the street markets that popped up every day.

And then, when I did come back in 1990, Jacques Pepin’s TV series, Today’s Gourmet, had started. I still think of that as a hugely influential thing for me. He cooked simple versions of mostly pretty classic French things, not haute cuisine, but more country everyday cooking, but he didn’t talk down to anybody. I think I learned a lot of technique just by watching Jacques and his calm, confident teaching mannerism on television.

HT: So, today, when you’re thinking about recipes, how do you come up with stuff? Is it pretty ingredient driven?

BL: I would say it’s pretty much ingredient driven – that’s really the thrust of the whole cookbook, taking your lead from the ingredients. You know, I wrote somewhere in the book’s introduction about “gathering food with purpose and intent,” which was quoted back to me on the radio the other day and I thought, “Oh, God, that sounds really serious.” That’s true, in a certain sense, but it leaves out the aspect of serendipity that I think really makes it fun. I might go to the farmers market, the co-op, Clancey’s, with an idea for a meal, and they might not have what I’m looking for — they might be out of lamb shanks, it might be too early for corn, or maybe everything I want might be there, but something else just catches my eye. I think it’s just fun to let the market and your own enthusiasm lead you in your cooking.

Pickled Red Cabbage Wedges (Reconstructed Coleslaw) with Blue Cheese Dressing

(Reprinted from Trout Caviar: Recipes from a Northern Forager by Brett Laidlaw, with permission from the Minnesota Historical Society Press)

Serves 4

Chefs are all the time “deconstructing” dishes; I think it’s about time some things got reconstructed. This winter salad brings a lot of crunch and interest to a dark day’s plate.

¼ large head red cabbage

1½ C warm water

1 Tbsp salt

2 Tbsp sugar

½ C plus 1 tablespoon cider vinegar, divided

1 small clove garlic, minced

2 tsp minced shallot

1½ ounces blue cheese, crumbled (about ⅓ cup)

¼ C heavy cream

2 Tbsp mayonnaise

2 tsp minced carrot

1 cornichon, minced (about 1 tablespoon)

Freshly ground black pepper

Leaves stripped from 2 sprigs fresh thyme

Cut the cabbage into 4 wedges, taking care to keep the leaves connected at the root end. Combine the water, salt, sugar, and ½ cup of the vinegar in a pan large enough to hold the cabbage. Bring the brine to a boil, add the cabbage, and simmer for 3 minutes. Remove from heat and let the cabbage cool in the brine. Set aside 2 tablespoons brine. Combine the remaining ingredients (garlic through thyme), including reserved brine and the remaining tablespoon cider vinegar, and mix well. Divide the cabbage wedges among 4 plates and swipe a spoonful of dressing across the middle of each. Serve with bread to mop up extra dressing.

Comments are closed.