PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY OF UW-PRESS / CHRIS HYNES EXCEPT AUTOR PORTRAIT BY MAUREEN JANSON HEINZ

Whenever I want to know what’s going on with food and restaurants in my hometown of Madison, Wisconsin, I read whatever’s new by Lindsay Christians. Christians is the food editor of The Capital Times, and she’s equally capable of deconstructing the flavor components of high-end ramen as she is of documenting difficult reckonings in an industry that’s currently full of them. In the world of Madison food media she has long played a crucial utility infielder role, staying on top of everything from restaurant openings to book releases to breaking news.

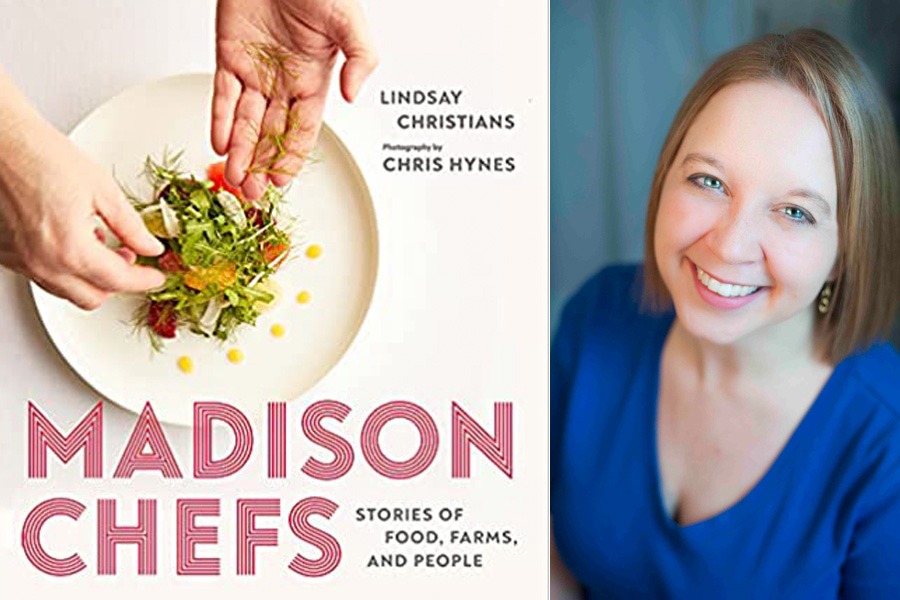

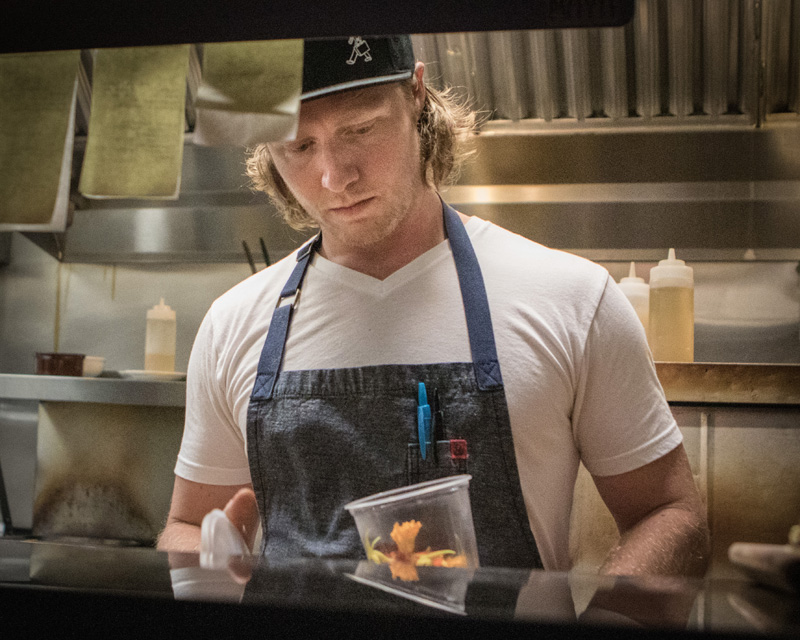

Christians’s command of both the light and the substantial is key to making the newly released “Madison Chefs” the thoroughly engaging book that it is. “Madison Chefs” is a series of rich profiles of eight of Madison’s leading chefs, illustrated by the gimlet-eyed photography of Chris Hynes. It turns on big personalities – people like Tory Miller of L’Etoile, Jonny Hunter of Underground Food Collective, and Tami Lax of Harvest and The Old Fashioned – and Christians renders them boldly, warts and all. But it also revolves around big, bright flavors and culinary leaps of imagination, and those come through equally vividly in anecdotes, photos, and recipes.

A reader of “Madison Chefs” becomes aware not just of eight individual stories, but of the complex networks of friends, mentors, rivals, and apprentices who support the leading players.

“I really wanted to emphasize that no person is an island, no restaurant is an island,” says Christians. “Madison Chefs” draws its power from good food and Wisconsin farms, but it also works because Christians has painted a clear and nuanced picture of complicated culinary systems.

“Of all the things I get to do in this job, I love reporting, I love calling people and asking them questions, that’s my favorite thing,” she says. “So you have a chef at the center of a chapter, but then I wanted to talk to every one of their mentors, I wanted to talk with their team, their staff, I wanted to talk to the places they worked before, and to the farmers they worked most closely with. And when you start doing that, that web of connections starts to emerge.”

’77 SQUARE MILES SURROUNDED BY REALITY’

Defining Madison is a Wisconsin parlor game that never quite goes out of style. In 2013, the old chestnut “77 square miles surrounded by reality” was proposed (and rejected) as the city’s motto, a fight that pointed up the emotionally volatile nature of the place. Depending on who you talk to, Madison is paradise on Earth or a bunch of terrible liberals who are ruining Wisconsin, or maybe both.

But for culinary purposes, says Christians, the key that unlocks the city is its relationship to agriculture. “The Dane County Farmers Market, for what is it – 50? 60 years now? – has been the largest producer-only farmers market in the country,” says Christians. “It’s really driven a lot of Madison’s ability to have culinary innovation that’s very specific to this place.”

That portal linking an internationally connected college town to the countryside around it, says Christians, is key. “[Author] Terese Allen talks about ‘rooted cosmopolitanism,’ this idea that we’re very connected to the farms around us, but we also have people coming to the university and capitol from all over. It’s a combination that’s a little bit the best of both worlds.”

SMALL CITY, BIG RISKS

For Christians, writing “Madison Chefs” was a chance to take the pulse of the food industry in one of Wisconsin’s brightest spots for gastronomy. That meant documenting her chef subjects’ biggest risks – the swings (not all of which connect) that define them as professionals and people.

“One big one would be Dan Fox and Willow Creek Farm,” says Christians. “Becoming a pig farmer wasn’t something he trained to do. He just got really into pig farms and farming.”

Christians recalls a visit to several of Fox’s farms during a cold snap (“It was incredibly, deeply, bone-chillingly cold!”) in January of 2018.

“We were out there and he was pointing out, ‘This pig is a cross between this kind of pig and this other kind of pig…’ and talking about coming up with a Wisconsin heritage breed of pig, which is just a cool idea. […] It was interesting to hear him talk about this circuitous place he came to – pig farming, of all places! He trained and staged around Europe as a fine dining chef, very intense… yet here he was out on this Amish farm where his pigs are.”

Similarly, she recalls, Jonny Hunter got into a particular variety of pepper to the point of recruiting farmers to grow it and buying out their crops. Which dovetailed, in part, with Hunter’s interest in seed saving, and the impact of climate change on agriculture, and his work with the University of Wisconsin system’s Seed to Kitchen program. Again: crucial connections woven together to tell a bigger story.

“Madison is a relatively small city,” says Christians. “There are only a handful of restaurants that are at the higher end. But there’s no one person in this who is pulling themselves up by their own bootstraps and doing it solo. I think that’s fiction, and I think it’s a dangerous fiction. It’s very American though, to imagine that we’re going to pull ourselves up without help – but nobody does that.”

“Madison Chefs: Stories of Food, Farms, and People,” by Lindsay Christians with Photography by Chris Hynes, University of Wisconsin Press, 219pp