She just won’t come in. Mike Lorentz and I survey the scene from a viewing deck above the kill floor of the meat processing plant he and his brother Rob own. Thirty to forty animals a day come through here, destined to be someone’s pork roast, ribeye, or hamburger, but this one refuses to play along. The cow stands just outside the knock box, the pen which holds the animal closely so that the stunner can do his job and render her senseless before she is bled out and begins the transition from animal to meat. We can’t hear the stunner, but we can see him leaning over the knock box, waving his arms, shaking a rattle stick to startle the cow into movement. He has a prod (not an electric one; Mike can’t remember the last time they used one of those) that he taps her back and sides with, to again try to jolt her to move forward. But she won’t go. So in the end, he takes the captive bolt gun, leans over the far end of the pen one last time, and fires. The cow collapses in the entryway, and all four people working on the kill floor leave their stations to drag what is now perhaps 1,200 pounds of dead weight into the room.

Between the coaxing and the hauling, no small feat even for four men toughened by daily eight-hour shifts of manual labor, just getting the cow into the room takes about fifteen minutes. “Can you imagine if you had to get 5,000 done today,” Mike turns to me and says, referring to the major processors that produce most of the meat in this country, “you couldn’t afford the luxury of this much time…but here, this is the way we do things. It’s inconvenient, it’s a lot more work for the guys to do it this way, but they did it instead of just beating on the animal.”

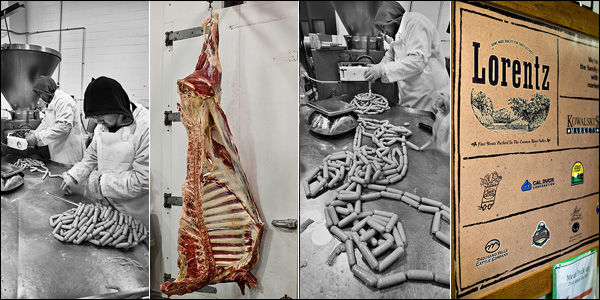

Lorentz Meats has been doing things a little bit differently from the mainstream ever since the Lorentz family started the business in Cannon Falls in 1967. During decades when the industry’s focus was on building ever-bigger plants to handle the mass production of inexpensive meat, Lorentz stayed small, partnering with local farmers who might only bring one animal a month to slaughter. It wasn’t until the year 2000 that the Lorentz brothers, who had taken over the family business from their parents a few years before, built a bigger, more modern plant. With the new building, they were able to meet requirements for USDA approval, which in addition to their organic certification made them an attractive partner for farms in the booming market for natural and organic meat. Now they process about 10,000 animals a year with a staff of 60 employees.

But as they’ve grown – and they’re still tiny relative to the Cargills and Smithfields of the world – they’ve stayed unique. The existence of the viewing deck on which Mike and I stand is ample evidence of that. The Lorentz brothers built it so that their customers could verify with their own eyes how Lorentz goes about its business. What’s more, they make it available to anyone who wants to drive out to Cannon Falls and see for themselves what the slaughter and processing of meat entails. In an industry whose main marketing strategy is to stay out of the public eye, this sort of transparency is unheard of. It won kudos from none other than Michael Pollan, who gave Lorentz an honorable mention for what he calls their “glass abattoir” in the foodie bible The Omnivore’s Dilemma. Partly as a result of this exposure, Lorentz gets hundreds of visits a year from people curious about just how their food makes it to their table.

Of course, that’s not to say that everyone who wants to eat natural or organic or humanely-raised food wishes to be personally acquainted with every detail of its production. However, even those who don’t want to think about what happens to their grass-fed beef after it’s done frolicking on the green pastures of home would probably like to assume that its end befitted its life. Lorentz Meats is there to ensure that that happens; to complete the circle between the good farm and the consumer who goes out of his way to support it.

To do so, Lorentz must offer the whole package: high animal welfare standards; an unimpeachably clean and healthy environment; and the type of small-scale, customized service that farmers who may only process one animal a week require. Lorentz does it all. To protect animal welfare, Lorentz designed the plant in accordance with the advice of animal welfare expert Temple Grandin, and Lorentz uses Grandin’s videos to train employees on animal handling. The workers on the kill floor know that they have to check for eye movement to tell whether the animal is insensible to pain before they take the next step, a precaution which Mike suspects is unrealistic at conventional high-volume plants where “…before you even get a chance to look at it, it’s moving down the line.” Employees who don’t adhere to Lorentz’s high standards for animal welfare are not tolerated. Once, Mike notes, they had a worker who needlessly poked at an animal. That employee lost his job.

Lorentz is also serious about hygiene, which is top-of-mind for many consumers who read reports like the recent New York Times article about E. coli contamination in ground beef. Mike’s philosophy on keeping meat clean is just that – you have to keep meat clean, not let it get dirty and then try to wash it off later. That’s trickier than it sounds. Although the inside of an animal’s body is sterile, the outside is anything but. If feces from the surface of the hide touch the meat inside, you’ve got a problem. So the skinning process, where the hide is separated from the meat, is where hygiene really starts to matter.

To skin an animal, a worker makes a slit up the belly, then peels the hide back with one hand as he slides the knife along the opening to release more skin. If at any time part of the hide brushes the meat, or the worker’s “peeling” hand touches the carcass, you’ve got potential contamination. So, in addition to being as careful as possible during the skinning, the workers are constantly trimming tiny pieces of meat off the skinned carcass afterward, as it goes through the stages of evisceration, splitting and quartering. Their eyes are trained to catch every speck of dirt and cut it off before it gets into the cooler.

For a big processor whose profits depend on driving maximum yield, however, every scrap of meat cut off is a penny that should have been pinched. So instead of keeping the meat clean in the first place by throwing away the dirty bits, they try to rinse the dirt off with acid and hot water washes. Implicitly recognizing that this doesn’t quite cut it, however, the industry advocates using an antimicrobial bath on the pieces from the edges of the carcass that go into ground beef, as yet one more chemical line of defense against contamination. Lorentz had never used chemical washes – and had never had E. coli contamination, either – but several years ago bowed to pressure from the USDA to get with the program. It now uses two organic-compliant washes, not instead of but in addition to its trimming procedures.

This focus on the integrity of their product makes Lorentz a natural partner to farmers who market their meat as organic, healthy, or humanely-raised. But many farmers in the Upper Midwest who produce this kind of meat are also small, and require a partner who can work at their scale. Lorentz fulfills this need as well. Dave Minar, who runs Cedar Summit Dairy in New Prague, processes a couple dozen hogs and about thirty beef cattle a year with Lorentz, which comes to about one animal a week. Big processors don’t have the economic incentive to take on such small orders, which gum up the economies of scale they rely on to make money. Processing one steer for a customer like Cedar Summit means tracking the parts of that animal as they filter through to separate areas of the plant for steaks, sausages, and ground beef, and then bringing them all back together again for packaging and storage. Processing in a large plant moves in the exact opposite direction, often combining meat from different animals, farms, and even other sub-processing facilities to create a generic finished product. Minar is adamant that he couldn’t work with the big guys: “They’re all about the bottom line, mass production. Lorentz is a unique business; they cater to small farms that want to market their products directly to consumers.” With Lorentz’s partnership, Cedar Summit can supplement their dairy business with a small volume of pork and beef sales at their on-farm shop.

Years ago, says Mike Lorentz, small local farms like Cedar Summit made up all of Lorentz’s business. They still comprise about twenty percent of it, but as the market for organic and humanely-raised meats has grown, Lorentz has also taken on some pretty big accounts. So while Wednesdays are still dedicated to one-off orders from small farms, the other days of the week are spent processing cattle for the likes of Thousand Hills Cattle Company, Organic Valley, and High Plains Bison. None of these companies is a Tyson, but they’re all big names in the world of niche meat and dairy production. And just like the little guys, they need partners like Lorentz to stay in business themselves. Todd Churchill of Thousand Hills, all of whose 1,100 cattle a year are processed at Lorentz, has nothing but praise for them: “In my opinion, they’ve built the safest, cleanest, best-operated plant in the country, which enables me to make a product that’s far above average.” If Lorentz hadn’t been in existence, Todd says bluntly, he wouldn’t have started Thousand Hills in 2003. “Lorentz’s plant was built not just with efficiency, but with quality, in mind. Unlike the large processors, who try to band-aid the quality later.” For a brand like Thousand Hills whose reputation is built on quality, a partner like Lorentz completes the package.

Despite Mike Lorentz’s reservations about the size and scale of the big processors in his industry, he does believe in partnering with some of these larger brands in the niche meat market. “It’s not that small equals good and big equals bad,” he notes. “We’ve seen some of the most egregious animal handling by small organic farms,” who, in their zeal to save the world, “sometimes forget about the little details.” On the other hand, he points out, bigger companies have certain upsides. Importantly, they have the ability to make premium products available to consumers at a reasonable cost. Here he’s referring not just to the Organic Valleys of the world, but to the retailers who carry them. He points to a ten-pound pack of High Plains Bison steak that carries a $47 price tag: “Specialty retailers in the Twin Cities might sell this for $8 a pound. But this steak’s going to Costco…and they’re selling it for $4.70 a pound.” Of course, there’s a method to Costco’s madness; for one thing, they require that you buy ten pounds, which is enough bison to drown a one- or two-person household. Plus they charge membership dues. But the point is, Costco’s size means it can take advantage of an efficient distribution network and high volumes of customer traffic to make niche products available to the vast market that is Middle America.

Nonetheless, whether you buy it at Costco or not, you’re still going to pay more for it than you would for conventionally raised and processed meat. Mike Lorentz echoes several others in the business when he estimates that the consumer can pay up to twice as much for organic or humanely-raised meat that is slaughtered and processed according to standards as high as Lorentz’s. That price tag reflects the true cost of the labor and time it takes to manage the entire lifecycle of an animal without the dubious aid of subsidized feed, antibiotics, and layers of chemical sanitizers. But in the words of Todd Churchill, you don’t expect to buy a Mercedes for the price of a Chevy. Mike Lorentz and his compatriots just have to hope that the consumer can distinguish meats as readily as cars.

I asked Mike whether, if he could run one of those 5000-animal-a-day processing plants, he would. “No,” he replied, “I don’t know the right word to describe them… it’s such a using market. They use the staff up, they use the animals up. It’s all about least cost, wringing every dollar out of it possible. It’s just not interesting to me.” Luckily what does interest Mike and his brother Rob benefits the farmers and consumers whom they serve: good meat, done right.

Lorentz Meats sells antibiotic-free, nitrite-free pork sausage under its own label at Twin Cities area co-ops, including Linden Hills and the Wedge. You can find Organic Valley (under the co-brand Organic Prairie) and Thousand Hills Cattle Company meats at Lunds & Byerly’s, Kowalski’s, and many co-ops. High Plains Bison products are sold through direct mail and select retailers, including Costco.

Angelique Chao writes about animal welfare and food ethics at Eating Animals.

I absolutely love Lorentz Meats and Thousand Hills Cattle Company. I’ve been in the Lorentz Meats facility and seen how they work. They have great products (I love their bacon), they are run in a way that I appreciate, and they are local. They are a win!

Good on Lorentz Meats. If only the rest of our agricultural system was as transparent and open as they are.

Thanks for such a thorough article about an ethical business.

Great article and fabulous photographs!

When I toured Lorentz this fall, my heart raced with anxious anticipation as I entered the viewing room. But in a matter of minutes, I was at ease, pleasantly surprised by the cleanliness and efficiency of each slaughter.

Thanks for capturing the method and the meaning so well. Great writing. Great photography. Love Heavy Table.

Awesome photos…who knew meat processing could actually look appetizing

I just love the products! Im so Proud we still have productive, caring business. This is what America is all about, thankyour for all your hard work.

Thanks for sharing this! I’ve seen Organic Prairie at Cub and wondered where it came from. And I’ve been buying Thousand Hills beef from Target. I’m in the TC, so I’m excited to have these great products so close to home. I’d love to see more products in those stores. So far I’ve only found ground beef and no pork products.

I’m far away from any of the co-ops but please email me if you begin to sell your pork products in the west metro. I’ll go get some. :)