“I simply want to live in the place with the best food in the world.” — Eric Dregni

With fall upon us and herb gardens bolting all over the city, it’s not uncommon to hear local gardeners chattering obsessively about pesto: basil pesto, parsley pesto, dill pesto, arugula pesto, thyme-tarragon pesto…

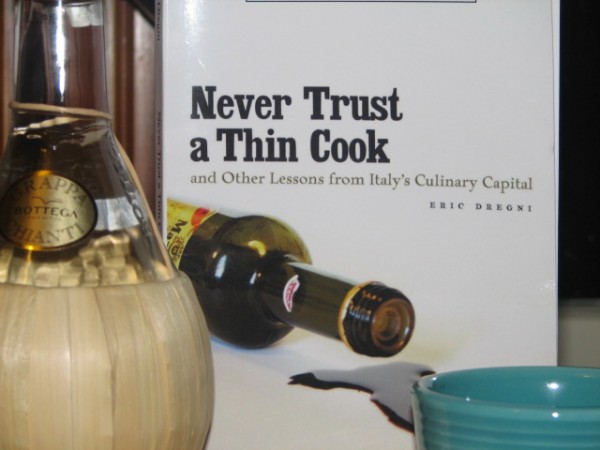

Thus, when Eric Dregni writes of creamy, white pesto Modenese — made with ground garlic, rosemary, and pig fat — in his new book Never Trust a Thin Cook and Other Lessons from Italy’s Culinary Capital, it is a matter of great interest. Well, curiosity and then mild frustration — for the author does not tell us how it is made or how it tastes. Nor will he describe the flavor of caffé corretto (“coffee with a healthy shot of grappa [Italian firewater]”) or the mouthfeel of cervello di maiale (pig brains), for example.

Yet it’s easy to set aside the longing for a vicarious gustatory experience and give way to the Dregni’s considerable storytelling ability.

Never Trust a Thin Cook (University of Minnesota Press, $22.95, 240 pages) is billed as a food-obsessed chronicle of a Minnesotan’s adventures in Modena, Italy, and it is that, but while the author does eat himself silly, what his lighthearted essays more vividly capture are the people, the culture, and philosophy behind the food.

The premise of the book is that Dregni and his girlfriend Katy, a fellow Minnesotan, will quit their jobs and move to Modena for two years. Katy will teach English; Dregni, an assistant professor of English at Concordia University, will write an “American in Italy” column for a weekly paper. “Most of all, I hope to reveal the tricks of making tortellini, indulge in generous helpings of prosciutto and Parmigiano-Reggiano, and write about the good life in Italy,” Dregni writes.

M.F.K Fisher once wrote that the mark of a true gourmet is a complete lack of caution. Dregni seems to apply that philosophy to all of life, at least in Modena, putting himself at the mercy of come what may, whether it’s accepting a bite of something dubious or an impromptu speaking engagement on a foreign subject. The resulting essays provide a rich, if sometimes absurd, look at many aspects of Italian life: sex, politics, taxes, postal service, bikes, opera, soccer, superstition — and of course, food.

Modena is well known for its balsamic vinegar. In a scene that is typical of Italy and the book, Dregni visits the acetaio of Franco, a pet store owner, who brews balsamic vinegar in musty wooden barrels — each a different size and wood — stored in his attic.

The windows are wide open, and Franco explains, “Vinegar is alive and must be properly aged. Besides, I love it when the whole house has this fantastic odor of vinegar…” he says, delighted. I’m sure we’ll never be able to wash the acidic, molasses smell out of our clothes.

Each year, Dregni writes, Franco and his wife boil white Trebbiano wine and pour it into the largest of the barrels to make up for evaporation, then systematically decant the black vinegar from the larger barrels to the smallest — a process that yields only two liters of balsamic a year. And, each year, a vinegar expert visits to ensure nothing has gone awry.

“It’s a tense time,” Franco tells me. “If you don’t follow the process, your vinegar will be ruined… then you have to throw away all your bad vinegar, which was begun more than a hundred years ago. This is a disaster for the family.”

This pride of food tradition, and the generosity it inspires, is a theme throughout the book. In another essay, a friend’s nonna, or grandmother, teaches Katy how to roll out and form homemade pasta. As they cook, she passes along technique and rules — tortellini must have meat, tortelloni must not — and in the end, she gives Katy her pasta machine, telling her that to get good at pasta you need to make it once a week. “In 1973, they gave me this machine, which is now a relic, but I’ve never used it! These machines change the flavor of the pasta so it comes out tough. I’m going to give it to you, but I advise you never to use it!”

Not every interaction is so earnest. When the paper’s wages turn out to be too meager to live on, Dregni starts teaching English. Much of the book is dedicated to his students and some of its funnier moments are born from their malaprops and verbal slip-ups.

I say, “fax.”

She says, “fux.”

“Fax.”

“Fux.”

I choose a different tack and explain that we also use “fax” as a verb. She responds, “Oh, you use ‘fux’ as a verb? So when I call on the telephone to a client I can say, ‘I want to fux you’!”

Overall, Never Trust a Thin Cook is a sweetly humorous book and delightful read. Oh, what this envious reader would give for a few recipes and well-wrought descriptions, but in their place, some choice lessons:

Superstitions: “While spilling salt is bad news, accidentally tipping over your wine glass is good luck. To make sure this good fortune sticks, dab your finger in the wine and put a little behind your ear.”

Driving: “Passing on the right. You can do anything to get past all those cars in front of you. If there’s no room, use the sidewalk. Around blind corners, just honk and go. Especially dangerous curves are indicated with flowers and crosses.”

Nutella: “Maybe I’m more Genovese than Napoletano… I never share my Nutella. It’s like underwear, there are certain things you don’t share with friends.”

Thanks for this review- sounds like a fun book, in spite of missing the recipes. I’ll have to read it to find out the difference between bad luck for spilling salt and good luck for throwing some salt over your shoulder as in Rachael Ray..